23 Jan Fiji — Playing with Fire in Fiji

When I was in high school, it never occurred to me to want to go to high school in Fiji. I just wanted to be in Fiji. Then when I actually saw Fiji, high school there seemed like an excellent idea.

Peg and I had scored a deal at a dive resort. An unusually intimate dive resort as it turned out, because the only other guest was a lady from Switzerland who left a couple of days later. After that, it was just us. And the couple from South Africa who prepared the food and guided us about the reef. And the gardener.

The gardener may have done some gardening, I never noticed. What I did notice was that he spent his evenings in a shed quaffing kava, and that It only seemed multicultural of me to join him.

The word “kava” comes from the Polynesian for “bitter,” but that’s not the way it tasted to me. To me, it was more the flavor of dirt mixed with fresh rainwater, but nobody drinks kava for the taste. It’s like fortified wine that way. People drink it because of how it makes them feel, and kava is both psychoactive and narcotic. Not very much of either, but enough to create bonds of fellow-feeling between, say, a gardener and a complete stranger who wandered into his shed.

Traditionally, it’s made by women chewing roots, then spitting the pulp into strainers, squeezing out the saliva and whatever juice there is into bowls, and adding water.

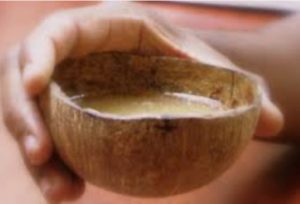

That doesn’t sound all that sanitary to Western ears but, what the hey? Who ever heard of catching something from a Pacific Islander? They’re the ones who catch things from us. So, armed with the latest in evidence-based, public health reasoning, I took a swig when the gardener passed the cocoanut shell, handed back the shell, and round and round the kava went.

That’s pretty much what I remember: a dimly lit shed, the gardener dipping kava from a wood bowl, and passing a cocoanut shell. That, and the taste of puddle. It’s all pretty blurry.

What I remember for sure is making my way through the beautiful, tropical night to Peggy and bed. And sleeping really well, which might have had something to do with the kava. But also might have had something to do with my blood being saturated with nitrogen from the day’s diving.

The diving in Fiji is pretty great if you don’t care about invisible seahorses. The lady from South Africa would glide up to a piece of seaweed, point at something the size of a paramecium, and Peggy would join her and give the okay sign. The lady would okay back, and the two would bob and blow bubbles together. Then I’d swim over and, stare as I might, the seaweed would just look like seaweed. Back on the boat the conversation would be nothing but seahorse all the way to the dock. After one too many invisible seahorses, even I was ready to spend a day ashore.

It being the end of November, we crashed a high school graduation. Whoever the school imagined we were, they were welcoming and made places for us on a woven mat beneath a thatched shelter along the sidelines of an athletic field, and it was way more fun than any graduation we ever attended at home.

Instead of kids traipsing up one by one through a stuffy gym to receive their diplomas, the girls formed into lines on the far end of the field, the guys in lines in front of us, and they danced.

They danced for themselves. They danced for each other. They danced for their parents; for their school; for the people their people had once been, and for the people they could be again. They danced the kind of rhythmic, stomping, guttural, evocative dances redolent of sex and masculinity that must have driven missionaries into paroxysm of exorcisms.

So many boys in America spend decades trying to figure out how to be men, while those Fijians dancing in front of us . . . dancing at the end of their time in school . . . were celebrating the men they’d already become. Proud, joyous, strutting, powerful men carrying the heritage of their people in their young bodies. They carried other things as well. They carried spears, and the rows of dancers became ranks of warriors thrusting and lunging, prepared to protect their families and their society the way men have done for as long as there have been men.

It made me sad for my son who got busted with a Leatherman tool and I had to represent him the expulsion hearing. A by-god expulsion hearing over a Leatherman tool. The school was serious about it, too. Zero tolerance means zero tolerance.

I pointed out that the army taught me to kill people with a pencil. And was tempted to make an example of the principal right then and there, but thought better about and laid my sharpened number 2 on the table. “We have a written exception for those,” he told me, as if that made any sense at all . . . while in Fiji fully fledged men lunge and parry with spears as part of their graduation ceremonies. The whole charade makes me want to travel back in time and buy my son a Kentucky long rifle to keep in his locker.

Fire-walking wasn’t included in the ceremony and we had to go to another part of the island to see it. I have no idea why anybody would want to do something like that. It’s probably bound up with spirits or gods, or ancestors or some other kind of thing anthropologists talk about. But my guess is, it’s just a way to show off in front of the ladies.

The guys make a big deal out of building a fire and raking the coals, although you kind of worry about the grass skirts in a situation like that.

It was all plenty impressive, even if I couldn’t help thinking about sacred drinks containing psychotropic liquids laced with narcotics.

A hundred yards away, the ladies didn’t seem all that impressed. The fact is, they hardly seemed to notice. They sat in the grass and gossiped and wore little blue and yellow and red things sticking up from their heads that may have been special tropical flowers appropriate for attending fire dances but, from where we sat, looked like bubblegum balls bobbing on springs.

Every now and then, one would glance up to see what was going on with the guys. And, I’m pretty sure, to confirm that it was still going on and she and her sisters could keep chatting and not have to go back to chewing kava roots.

That’s the kind of thing feminists run on about, women chewing roots so men can party. But ask yourself, Who gets the better end of that deal? The guys swilling the watered-down version so they can walk over red-hot coals, or the ladies spending their days munching the real thing?

No Comments