25 Jul Chinese Ambassador – 4

When somebody has you to dinner, the only thing to do about it is to invite him to your place. The problem with having the Chinese ambassador to our house was that Peggy and I had come away with the impression that no member of the Chinese delegation, no matter how important, was ever allowed to be alone with foreigners. Maybe, even, especially the important ones. So we had to figure out whom else to invite.

The obvious choice was his wife, but she was in China. He was allowed to fly home once a year for a conjugal visit, but that was it. Sounded like a hostage situation to us, and I’m pretty sure it was. I never met the woman so there’s another possibility. The word at our embassy was that the Chinese ambassador was marked for greatness so, I suppose, he might have had the chops to put in a word with the higher-ups, strings had been pulled and, le voilà, “Sorry, Honey. They’re sending me to Botswana without you.” He’d given her a What-can-you-do? kind of shrug, and off he’d gone. It could have been that way, but I’m sticking with hostage until I hear different.

The Slender Man who’d accompanied the ambassador when he’d invited us to dinner would have been a candidate, but neither Peggy nor I had a clue who he was, so it was hard to invite him. In the end, she just told the ambassador to bring whomever he liked, and left it at that.

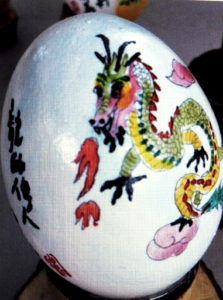

He showed up with his Political Officer, and the Political Officer brought Theresa. Actually, her name wasn’t Theresa, it was an unreadable series of Chinese glyphs, so she went by Theresa as a convenience to the rest of the world. The Political Officer, who wasn’t named Joe, introduced himself and handed Peggy an eggshell resting in a cleverly carved little stand. I didn’t know what Chinese Political Officers were supposed to do, but I had an idea what they did at the old Soviet embassies, and his job title made me curious about which arm of the Peoples’ Government was paying Joe’s salary.

The eggshell was delicately painted, and pretty, like something a maiden aunt might display in her curio cabinet, and Peggy and I liked it.

I think they had a closet full of the things back at the embassy, along with silk scarves and cleverly-carved pieces of wood for their diplomats to dip into when they got invited to dinner. If their embassy works anything like ours, there’s paperwork involved. After all, no country wants its ambassador spreading a blanket across the sidewalk and setting up an after-hours market in painted eggshells.

We didn’t know what to do with it and put it on the sideboard next to a flamboyantly carved, very explicit, very nude carving of a woman from the Kuban People of the Congo. An eggshell on a delicate stand made a nice contrast and I liked having it there until, one morning after a party, Peggy and I discovered it smashed into pieces and joked about the little recorder inside somebody had retrieved. Being bugged would have raised our status in the American community.

We had a friend who served for years in Moscow and hadn’t been bugged. Periodically he’d ask the embassy security people to sweep his apartment for bugs, only to have his hopes dashed. “I’m important, too,” he’d mutter to the walls, or the lamp, or anywhere else he thought a bug was entitled to be. “I’m important too.”

We had another friend, another diplomat type in Moscow, who really was important enough not only to be bugged, but to be tailed. The Russians weren’t particularly subtle about it, though. Or, maybe, our friend just wasn’t as important as he would have liked, because the guy they assigned to him didn’t seem very skilled. At any rate, our friend would come out of his apartment and there the guy would be, hiding his face in a newspaper across the street. When the Russian looked up, our friend would wave and, after a while, the Russian would wave back and off they’d go, our friend heading wherever it was he happened to be heading and the Russian following along at an indiscrete distance on the other side of the street.

Once, late in the evening in a shadowy part of town, our friend heard a commotion and turned to discover the Russian wasn’t on the other side of the street anymore, he was a few dozen yards behind beating the crap out of a young man. When he had the man crumpled on the sidewalk, he reached down and pulled something from his jacket, slapped the man a couple times in the face, then walked over to our friend and returned his wallet. The man was a pickpocket.

The night the Chinese came to our place I barbecued shrimp for dinner. Looking back, I think it must have seemed like a pretty crude way to fix a meal, just tossing shrimp over the coals, but all three were diplomats, at least the ambassador was a diplomat, and Joe and Theresa played along. Then, out of the blue, the ambassador launched into a defense of China’s one-child policy, although nobody had accused it of anything.

“If we hadn’t done something, we’d have a trillion people by now,” and we knew he was right. Still, the sudden way he brought it up made him seem defensive, as if he was the one who’d decided all those little girls would never be born. Later, he settled back into the flow of the conversation and asked Peggy about the Peace Corps. Seemed he wanted to start one of his own.

His plan was to bring in half-a-dozen highly skilled professionals . . . he was talking engineers, martial artists, people like that . . . and wanted tips on how to make it work.

These would be premium-grade volunteers. It sounded like they’d be good for Botswana and Peggy couldn’t think of any reason they’d be bad for America, so she gave him the best advice she could. “You have to integrate them into the community.”

“How do we do that?” The idea of actually associating with foreigners on any prolonged basis seemed well . . . foreign to him.

“Have them live in the villages and get to know people.”

“I was thinking they could come back at night and cook for each other. Then go out in the morning and . . . .”

Through some combination of a repressive government and an inward-looking culture, the Chinese did it that way all over Africa. Despite what the gentleman I spoke to at the Moon Party would have had me believe, they don’t even use local labor on the big public works projects they’ve become famous for, which doesn’t just rub Africans the wrong way, it makes the Chinese look like racists.

In Botswana they built three modern airports, and didn’t win any hearts and minds. Instead, Batswana muttered about political prisoners brought over as slave labor. “You can’t tell one Chinaman from another,” a Motswana would tell you, “when one of them dies they just bring in somebody else on the same visa.”

Also, the work is shabby. “The airports were falling apart before they were even finished,” is something else you hear.

And the Chinese don’t actually pay for it. What they do is lend the host country the money, use their own labor, do a crappy job and, in the cases where the host countries can’t repay the loan, demand political concessions. Which may have been the point all along.

“At the very least, your people need to get out into the villages,” Peggy told the ambassador.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“It’s the only way to keep them safe. People get to know them and look out for them. Every now and then one of our volunteers gets robbed, but she usually gets her things back. The neighbors know who did it, the police are on our side and . . . .”

“We haven’t had any luck with the police. When one of our people gets robbed . . . .”

“Your people get robbed?” That was hard to imagine with everybody locked inside the embassy compound at night.

“In every village,” the ambassador said. “My people are in every village and they’ve all been victims of crime. I talk to them when I go around the country.”

“The people in the villages aren’t your people. They’re from Malaysia or Singapore. Maybe the Philippines.”

“They’re Chinese, wherever they come from.”

“Wherever they came from, they’re citizens of Botswana now.”

“They never stop being Chinese,” the ambassador said, “and it’s my job to represent them,” articulating the same identity politics that the Chinese Communist Party is happy to impose on Hong Kongers and Taiwanese and Tibetans. “They leave China with five pula in their pockets and come to Botswana and turn it into seven and then ten and . . . .”

“Wait a minute. I . . .” I tried to think of some polite way to say this . . . “People can leave China?”

“Of course people can leave China,” the ambassador shot me a look like I’d accused him of representing Vietnam or, maybe, Cuba. And, over the years, a lot of people have left China. Until, now, Chinese are scattered all over Africa.

In every dusty village in the Kgalagadi, places you aren’t even sure the government can get to, there’s a Chinaman selling lightbulbs and screwdrivers and cheap clothes out of little establishments people call China Shops: the village stores that generations of East Indians and Pakistanis had run before the Chinese put them out of business. Thinking about the Chinese coming to Africa made me wonder how many Africans, or people from any other country for that matter, ever imagined they’d have a better life by moving to China. But I didn’t ask that.

When the time came to go home, the person who wasn’t Joe thanked us for the “genuine ethnic American meal,” and promised to have us back to dinner, which he and the person who wasn’t Theresa and the ambassador did . . . at a very out-of-the-way Chinese restaurant in an unlikely part of town.

No Comments