14 Jun Kalahari Desert 3 — Bushmen Dance Festival

Every now and then Bushman who aren’t incarcerated in boarding schools get together and dance for each other. But only every now and then because any event involving Bushmen is difficult to organize.

Bushmen don’t take kindly to people with pretensions of leadership. When a man goes out on a hunt, the arrows he carries don’t belong to him, they belong to other people. When he returns with news of a dead gemsbok, he’s not the one who gets the credit. The kill goes to the person who owns the arrow. It can be a four-year-old girl, doesn’t matter. The gemsbok is hers. That way, no matter how skilled a hunter is, he never becomes more important than anybody else.

Whatever Bushmen may be, they aren’t harmless. That slander got started when a Massachusetts woman filled with love and understanding spent too long in the Kgalagadi sun without taking off their Rousseau-colored glasses, then wrote a book entitled, in a peace and love kind of way, The Harmless People. She came to this conclusion because she’d never seen a Bushman raise his hand against another. But that was just a statistical thing. Bushmen lived in such small groups that a single killing every few decades translated into a higher murder rate than inner-city Chicago.

Sudden-death-wise, Bushmen may be the most heavily armed people the world has ever seen. Which automatically makes them very accommodating in their social dealings. It also makes them the most egalitarian. If somebody tries to tell them what to do, they laugh at him. If he doesn’t give it a rest, he gets nicked with an arrow, and a Bushman arrow is nothing you want to get nicked with. The poison on a Bushman arrow is so powerful that, if someone tosses one on the fire, you die from the smoke. And everybody has arrows, even four-year-old girls.

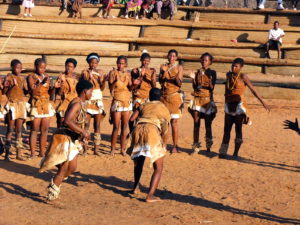

Trying to agree on anything by consensus, even dance festivals, can be a bitch, especially when the people who need to do the consensusing are spread across a million square miles of Southern Africa and speak languages that don’t even remotely resemble one another. Years when the dance festivals manage to happen, Bushman come to the Kgalagadi from Angola and Namibia, from South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Malawi, from Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia to strut their stuff for each other. Some years outsiders like Peggy and me are allowed to watch.

The dancing takes place in a small arena scooped out of the Kgalagadi and lined with logs for seats. Between the logs, reed mats keep the sand from spilling through.

They have all sorts of animal-related dances . . . giraffe dances. Lion Dances. Buffalo dances. Leopard dances. Impala dances. Leopard-hunting-impala dances. There are healing dances designed to heal each other, and those of us watching.

Some of the dancers weren’t wearing anything more than what looked like handkerchiefs around their hips, the girls throwing back their shoulders and swinging their breasts, making exactly the same moves I’d seen at parties in North Carolina, filling the night with the life bursting from their exuberant youth,

giving the finger to mortality in the way humans have done since before we were human.

To my eye, the dances didn’t look all that different. A lion dance from Angola seemed like a leopard dance from Mozambique. At the time, I thought that was disappointing but, now, I’m not so sure. Now it seems to me there’s more coherence between these fragmented peoples than you’d expect. These dances, I’ve come to believe, are a sign of the endurance of the culture. And of the people who dance them.

At night there were trance dances where lines of people snaked around a fire. The dancers were quick and lithe, a couple of dozen wiry young men and slender, athletic women, stomping and throwing their arms into the air. Then circling back to our side of the fire, silhouetted against the sparks showering into the night.

They didn’t all dance at once. Just twelve or fifteen at a time while the others sat like kids around a campfire. Then, in ones and twos when the spirit moved them, they stood and joined in. To be replaced, sometimes, by a dancer or two who would give a jerk as if they’d been overtaken by a trance, and collapse back into the ring of sitting people.

It was if we could see back in time to the wildness Africa had been, we had all been, but only if we squinted. And, then, only a little, like looking at a piece of taxidermy and trying to imagine the heated blood that once flowed through the animal: the wild power of the cape buffalo, its bellows and smells and quick temper; the sudden lunge of the leopard or the fluid grace of the impala. These dances, these people, the people we were when we danced the same dances, are not meant to be seen in arenas by those who politely clap, and then go our own ways.

The first year we went, the master of ceremonies was a woman, and she gave the lie to everything I thought I knew about Bushman leadership.

She was smart and assertive and precise and born for the corner office, if only Bushman had a place for such things, and Botswana had a place for Bushmen, and she had the whole world in her face. You could see Chinese there, Chechen and Czech, Choctaw and Chilean and Chané. Gazing at her was like gazing at all the people we’d become since we wandered out of Africa.

Three years later when the festival was held again, the dances were the same, animal dances and hunt dances and healing dances and trance dances. There was a dance with a tall witch doctor with animal tails in his hair and pelts and straw around his waist, but the dances weren’t so much for the Bushmen anymore. The future president was there, sitting in a little shaded area at the end of the arena, and the government had started billing the affair as a tourist attraction, trying to lure its own people to attend.

Give them a feel for the picturesqueness of their country, I suppose. Like the Genuine Indians who used to greet passengers when the Great Northern arrived in Glacier Park. In place of the smart, assertive, precise woman who’d run the show before, the master of ceremonies was Tswana, sleek and sure of himself the way government officials can be. And patronizing in the way kindergarten teachers sometimes talk to grownups. He introduced the dancers in Setswana, which blew right by the few white people there. And, I imagine, almost all of the Bushmen. Every now and then a drunken Motswana would get up and join in one of the dances. Come midnight we heard drums from outside the stadium and went to see.

Off among the acacia trees were scores of fires, each with its own group of Bushmen. They’d set up a communal camp and were dancing for themselves.

In the dark of a desert night, it was as if the stars in the Milky Way had fallen to Earth, hundreds of sparks lighting the night. Cook fires, animals roasting, people from Zambia introducing themselves, sharing food with people from Swaziland. Angolans laughing and gesturing and trying to make themselves understood to people from the East Cape or Namaqualand. A culture knitting itself back together, if only for a night or two. A few Tswana had wandered in but, I’m pretty sure, we were the only whites. It was wonderful and ancient and made me feel as if I’d joined my own ancestors seventy-five-thousand years ago.

No Comments