12 Apr East Africa — Mooching along with a Pig Farmer – 3

We left Lake Turkana and worked our way north along streambeds. It had rained a lot, and we kept coming to marshy places where we had to back up and try again but, eventually, we found some tire tracks and followed them to where the trees opened into a clearing. People were milling around and there was a little shack that might have had something do with a border, and a guy in Western clothes who could have been a border official, and a cop with an AK47. That made it official, a cop with an AK47.

Tribesmen were there, too, migrating south with their wives and children. The men were wearing loincloths, the women weren’t, and the children weren’t even wearing that. And they were black, very black, which comes as a surprise to somebody used to Batswana. Batswana aren’t black. They’re a mellow kind of mocha but these guys, they were black. And they were carrying bundles which, I imagined, contained just about everything they owned except the carved, wooden stands the men laid their heads on when they slept, which they carried in their other hand. The cop with the AK47 motioned us to stop, and Western-Clothes-Guy waved us to get out.

They led us into the shack and closed the door. It was the kind of shack I wouldn’t have cared to go into if the guys inviting us inside had been caretakers at a set of ruins alongside Lake Turkana but, then, the caretaker hadn’t been carrying an AK47.

This was Ethiopia, the guy in Western clothes announced. We needed to pay fifty-five dollars. There was a desk inside the shack littered with little pink squares of paper. “And you’ll need to give the policeman fifteen dollars to escort you to Bako.” Bako was the village a hundred-and-fifty kilometers inside Ethiopia where we were supposed to check into the country.

“If we check in at Bako,” I asked, “why do we need to pay here?”

“Directive,” the man in Western clothes smiled. “A directive from Addis.”

“I would need . . .” there was something fishy about this “. . . to see that directive.”

“Here . . .” the guy in Western clothes handed me one of the squares of pink paper “. . . is a copy of the directive.”

Whatever it was, it didn’t have the air of an official government document. It just looked like a carbon of a receipt for something or other. No different than all the other little pink squares of paper scattered across the desk. Besides, it was written in Amharic, which I can speak none of and read even less. Amharic is like Arabic that way. The people who write it say they’re using letters, but you can’t prove it by me. They’re pretty, though, with graceful little loops and pleasant to look at.

“Satisfied?” the man in Western clothes asked.

“I have to check something,” I said, and slid back my chair and left the shack. We’d been in there a while, tribesmen were outside we hadn’t been introduced to, and being introduced to someone is one of the ways you keep him from robbing you. I’d gone out to introduce myself, but there wasn’t any need. The tribesmen had moved on, things seemed okay, and I went back into the shack. I left the door open this time, though. “Need to keep an eye on what’s happening out there,” I said.

Western-Clothes-Guy was looking subdued. The pig farmer told me later that, when I’d walked out, he’d gotten very nervous. White men are rich, he must have been thinking. No telling what he has in that . . . whatever it is . . . parked outside. Could be guided missiles, for all he knew.

“We’re not paying to get into the country,” I said, and the guy in Western clothes sagged a bit. Then regained his élan. “But you still need to pay the policeman fifteen dollars to guide you to Bako.”

“We got here without help from anybody,” I said. “Why would we pay him to take us to Bako?” I was being proactive with that. There was no way the pig farmer was going to pay money to . . . .

“We’ll pay it,” he said. At the time I thought it had something to do with the AK47.

AK47’s had a reputation when I was in Vietnam, and we all wanted one. Our rifles were touchy and tended to balk when you needed them most. Not so with AK47’s. You could run over an AK47 with a tank, bury it in the sand and, a year later, dig it up and shoot an American with it. Ak47’s, it was said, were unbreakable.

Somehow the cop had managed to break his. It was an accomplishment unparalleled in the lore of the Vietnam vet but, there it was. The magazine shoved into the rifle had a crack down the side. That thing wouldn’t have fired if he beat on it with a hammer. Which, from the looks of it, he already had.

I never got a clear answer as to whether the pig farmer had noticed the crack, but he had a much better reason for taking the cop along. “I didn’t know how to get to Bako,” he told me later.

After Bako, it was back on Africa Tracks. For the next few days everybody we passed looked like the tribesmen at the border, except they all looked different. Every few miles the hairstyles would change and the loincloths on the men would be arranged differently. This was Omo country, and it was just about the most wonderful part of Africa I ever drove through.

I think it was coming-of-age season because we passed group after group of girls, a dozen, fifteen at a time, always about the same age and under the care of an older lady. They were as fine and as beautifully arrayed as European princesses, only lovelier because there was nothing affected about them. Then, down the road, we’d pass another group of girls, just as lovely, just as decked out, but different. Different cloth. Different jewelry. Different hair.

Sometimes they weren’t girls, they were young men, and if I’d had a taste for young men I would have dropped off the trip right then. Their hair was twined with strands of silver, they had gorgeous silver bands shining against the black of their biceps, and loincloths of rich, complex material. They all carried weapons, but they didn’t look like real weapons, just small bows and elaborate, ceremonial knives. I would describe it further but my memory is unable to contain it all.

As we made our way upcountry the land began to dry out. Then it turned mountainous, the most mountainous land I ever saw.

The world’s most vertical desert

One day we drove all day and didn’t go more than about a-hundred-and-twenty-five kilometers. A mile straight up a ridge, another mile down to a dry valley and up again to another ridge. On the map we’d have done fifteen kilometers or so. Once, the road didn’t bother to go back down, it ran along the top of a knife’s edge with a mile-long drop on both sides. Other times we’d come to a rock slide and have to wait for a road crew to clear the road.

A road crew removing an impediment

The people up this way were different. They were light-skinned with high cheekbones like the Ethiopians of your imagination. Everywhere thronged with kids, with adults, with herds of animals.

I don’t know what that thing in the air is, either

It was hard to see how that could be possible, the land was so barren.

Also, in the more accessible parts up near Addis where the highway was paved, people slept in the road. I don’t mean on the shoulder, or near the edge, I mean in the middle. Apparently word had gotten around that anybody who lives through a night sleeping in the middle of a highway populated with African drivers must be immortal. And who doesn’t want to live forever?

When we arrived in Addis, Africa Tracks led us to the campground where the pig farmer planned to stop for the night. The thing was, it didn’t look like a campground. It looked like a preschool. We could glimpse swings and a sliding board and brightly-colored, junior-sized seesaws through the gate. Also, there was a guard who thought it was a preschool.

“Campground,” the pig farmer led the guard over to the GPS perched on the dashboard, “this is a campground.”

“Not campground,” the guard said, exhausting his fund of English.

“We won’t be any problem,” the pig farmer pointed toward the plastic duck with a saddle wobbling on a spring, “we’ll just park over there.”

“Not campground,” the guard tried again. Then launched into a couple of paragraphs of spirited Amharic.

“But we’re supposed to camp here,” the pig farmer said.

“I think,” I said, “it’s a preschool.

“The person who came this way before,” the pig farmer gestured at the Africa Tracks, “camped here.”

“Not campground,” the guard said, practicing his English.

“It has a Minnie Mouse painted on the wall,” I said, thinking that whoever it was who’d spent the night parked at a preschool might not be the most savory of role models. “And Donald.” And some character that could have been Pluto. At least it was brown and doggish, with a, whip-tail like a manta ray. In the end we wound up at a hotel.

A room cost twenty-five-dollars.

“We can’t keep paying out money like this,” the pig farmer said and slept in the guided-missile carrier in the parking lot to make his point.

The next morning we spent a couple of hours at an internet café, and connected back up with the rest of the world. That’s when the pig farmer discovered that his wife was planning to meet him in Alexandria, which was sooner than he’d planned. He’d enlisted her for Cyprus to accompany him on the Europe part of the trip, not to show up in Egypt.

She’d been okay with that, she hadn’t known that Alexandria was anything special. Just one more boring dot on the map to crossword her way across, until her hairdresser mentioned that, actually, Alexandria was one of the most interesting places in the world. Now she’d be joining him there, and the news threw his budget out of kilter. “I’m going to have to buy her a ticket to fly with me from Alexandria to Cyprus,” he looked crestfallen. “I wasn’t counting on that.”

“You haven’t seen her in eight weeks,” I said.

He gave a gloomy nod.

“Cyprus is right off the coast of Alexandria. Almost,” I said. “How much could a ticket cost?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I just wasn’t planning on having to . . . .”

Given my track record with marriages, I may not have been the best person in the world to proffer nuptial advice. Still, I could see where this was heading. “I would,” I said, “have a lot of trouble explaining to Peggy why I wouldn’t want to buy that ticket.”

“I guess,” he said. Lucky for him none of that turned out to be a problem because a few days later he almost died in Sudan, and flying his wife to Cyprus stopped being an issue.

Before he almost died, we toured around Addis admiring the socialist-realist sculpture left over from the time when the wag who ran the country concluded that linking hands with International Communism was just the thing to solve Africa’s problems. From there we headed north to admire the churches.

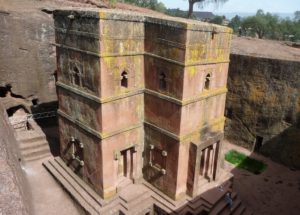

They have a lot of churches in Ethiopia, many of them carved out of rocks,

This used to be a rock

and priests inside,

A priest inside a rock

and we saw most of them.

They were interesting, in a cerebral sort of way. “Wow,” you say to yourself, “somebody carved a church out of a rock.” They smell like incense and have icons scattered about, but no stained glass because they’re inside rocks and the windows are just slits and it’s dark in there. And they aren’t very big because it takes a lot of work to carve a church out of a rock.

One of these churches has the Ark of the Covenant inside, but we didn’t see it. Only the Guardian of the Ark gets to do that and, according to National Geographic, he’s trained to kill with his bare hands, so we didn’t insist. The Ark arrived in Ethiopia in the baggage of Menelik. Menelik was born to the Queen of Sheba after she returned from her visit with King Solomon. When he grew up, he traveled to Jerusalem to study with his dad and, ungrateful son that that he was, swapped a copy of the Ark for the original and high-tailed it home. Ethiopians will tell you this. So will Indiana Jones.

What we were allowed to see

We poked around Northern Ethiopia until we came to Lake Tana, but it was just for old-time’s sake, for a past the pig farmer had been born too late to see, and for the Rudyard Kipling of the childhood still living inside me. Lake Tana is the source of the Blue Nile.

It used to tumble from the lake over a big waterfall, a grand entrance onto the stage of history. We’d seen pictures. But there wasn’t any waterfall the day we dropped by, just a huge, dry cliff with not much more water than you could squirt out of a fire hose.

What there was, was a power station somewhere, and the water had turned into a pipe dream.

No Comments