24 Oct Svalbard — Polar Bears at the Top of the World

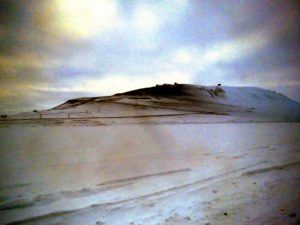

From the air, Svalbard looks pretty much the way I’ve always imagined Greenland would look

only more so, because practically the whole island of Greenland is to the south. Also, all of Siberia.

The two things I knew about Svalbard before Peg and I went were that it has the most polar bears of anywhere in the world – even including Churchill, Manitoba, where bears sashay down Main Street eating people’s dogs. And that Svalbard is so far up in the Arctic that its closer to the North Pole than the Arctic Circle. Which makes Longyearbyen, its capital, the northernmost city in the world. If you could call it a city.

With credentials like that, my seven-year-old self who does most of our travel planning insisted on visiting during the winter. For the true Svalbard experience. And to see the Northern lights. When Peg and I arrived, we checked into a room in a barracks that used to house coal miners . . . before they rioted over poor living conditions.

You can see why. Longyearbyen is gloomy in winter. Even its name struck us as apt for a place to be stuck on a yearlong contract digging coal. It took a while to discover that the town was named after John Munro Longyear, the Michigan timber baron who began mining operations in 1906.

You can get a dogsled

and mush past his coal works, or what might have been his coal works, they could have been Russian or British coal works, it’s hard to tell they’re so drifted with snow,

which is way fun and pretty much the only outdoor sport available. Unless you want to snowshoe up the mountain behind Longyearbyen to visit an ice cave.

Here’s a tip. If you do want to snowshoe up to the ice cave, wear snowshoes. The guide will bring them along and you can attach them to your boots and snowshoe on up. That is, you can attach them to your boots if you don’t happen to be wearing a pair of what look like gigantic Eskimo yak-skin boots you picked up from Capella’s to keep your feet warm up near the North Pole. Boots that are so big that even the largest snowshoes won’t fit, and you wind up with your snowshoes under your arm, sinking crotch-deep in fresh snow with each step, while everybody else gets farther and farther ahead of you.

Also, hire a guide because the mouth of the ice cave looks like the entrance to a dog house

and you’re going to trudge right on by and never notice.

I’d expected the ice cave to be prismatic inside: blue shattered into ultramarine and aqua, peacock and turquoise and cobalt, all dancing together under our headlamps. But, then, I’d never been in an ice cave before and I expected wrong. Mostly, the inside was ice-white where the lights shone

and dark and moist everywhere else, like spelunking in a freezer truck that needed to be defrosted.

Getting down from the mountain was no problem. We just flopped on our bellies and penguined almost to downtown Longyearbyen because, with Longyearbyen, there are no suburbs or used car lots or anything else to shield downtown from the howling Arctic wilderness.

Nothing can do that except the sun, and the day we swooshed down from the ice cave was the first day that the sun touched the steps of the old hospital. That’s a big deal day in Longyearbyen. There’s a Sun Festival, school children dress up like flowers and dance around, and the sun is officially declared returned. I would have liked to have seen that, but the sun didn’t mention it was coming and we spent the Festival doing ice-cave things.

There may have been Northern lights somewhere, but we wouldn’t know. It turns out the Northern lights are easier to see when it isn’t snowing all the time. Also, we should have given a bit more thought to that business about polar bears. Even my seven-year-old brain could have put it together. Bears. Winter. Hibernation. But I wasn’t any more analytical sitting at home by the fire planning the trip than I’d been about the consequences of not turning in my homework when I’d been seven.

Or, perhaps, there was a more grownup explanation. Polar bears are dying out. All the right people say so. The pack ice is melting and bears across the Arctic are falling into the water and starving to death. So, if you live in Churchill, Manitoba, keep a close eye on your pets. There will be a lot of hungry bears wading ashore.

The thing was, people in Svalbard didn’t seem particularly concerned about polar bears dying out. They were worried about being eaten. On Svalbard, you’re required by law to carry a high-powered rifle whenever you venture outside of town.

Off to book group, perhaps

You can carry them pretty much anywhere in town, too. Except inside the bank. They have stickers about that on the door.

L

ongyearbyen also has a university, the University Centre of Svalbard or, as the Toronto Star put it, the Harvard of the Arctic,

The Harvard of the Arctic

where the first day of student orientation is devoted to firearms training.

Once you qualify with the rifle you can study oceanography, but I wouldn’t. Oceanography involves SCUBA diving, and there are plenty of fine programs at places more equatorial than the Barents Sea to do that.

They have a nice museum at the university, though, a museum that focuses on geology and, this being Svalbard, the glaciers that sit on top of the geology. It was while I was reading about those glaciers that I came across this:

For the past 4000-5000 years the Earth has been subject to a marked cooling, which gradually has created better conditions for the growth of glaciers and permafrost. 5000 years ago the average temperature in Svalbard was around 4 degrees warmer than today. Then, one would probably have had to climb 200-400m up in the mountains in order to find permafrost, and many of today’s glaciers would not then have existed. The largest glaciers would have existed in a much reduced size. Many of Svalbard’s glaciers, therefore, are less than 3000-4000 years old.

Svalbard has gotten a lot of press lately for being the ground zero of global warming. Maybe, even, a bit above zero, sometimes. Degrees on Svalbard have shot up quicker than degrees anywhere else on earth, which got me to wondering about those polar bears. Polar bears have been floating around in the Arctic for something like 200,000 years. Even if Svalbard is warming up today, what were they floating on 5,000 years ago? The sign didn’t say, so I had to look it up on my own. And discovered that there are two schools of thought on the bear situation.

The first is the one you hear every time somebody waxes on about global warming. The other is that the bear population has exploded in recent years, mainly because of an international ban on polar bear hunting. When I tried to look up the exact numbers, I found some in the articles that thought there were more bears than ever. Twenty-five thousand, and climbing. Thirty-thousand, with populations of bears well established in dozens of locations throughout the polar region. The articles that thought the bears were dying out talked about pack ice. Less pack ice than ever. You can drive to the North Pole in your bass boat, if you want to.

Now I’m not a polar bear scientist and I’m not qualified to judge the quality of those articles, but it did strike me that one side was willing to commit to real numbers and the other, well, the other weaseled out with talk about pack ice.

No Comments