23 Feb Uganda — Chimpanzees in the Rain

In western Uganda between the Mountains of the Moon and Lake Albert, you come to the Kibale Forest . . . where people will take you to see chimpanzees.

Guaranteed.

“The forest is full of chimps,” they tell you. “Nobody has ever gone into the Kibale Forest and not seen chimps.

Other people were there the morning we showed up and they wanted to see chimps, too. But they were in groups and each group clustered around a different ranger, which left Peggy and me with our own, private guide. A personal tour of the chimpanzees. The only way things could have worked out better would have been if we’d actually seen chimps.

We followed the guide into the jungle. “Last night,” he pointed up into a tree, “chimps slept in that nest.” But they must have wandered off when morning came.

The jungle was steep and hilly and, being jungle, full of trees and ferns, vines to trip over and fallen logs and streams to cross. The guide tried mightily, but no chimps. Anywhere.

The story we heard was that there were chimpanzees in there

Come noon, all three of us were hungry, Peggy and I were getting blisters and feeling worn out. Eventually the guide gave up and led us back to the ranger station where I was looking forward to inquiring of the other tourists whether they’d seen chimps. I’d been caught up in that kind of scam before. But there weren’t any tourists there.

“The others were back here by 9:30,” the rangers told us. “Saw their chimps and were on their way.”

“All of them?”

“Except the ones who were back by nine.” The rangers looked embarrassed. “Nothing like this has ever happened before. “People always see chimps.”

They had a discussion among themselves, the head ranger stuck his neck out a bit, made an executive decision and announced that, since the honor of the entire chimpanzee reserve was at stake, he’d bend the rules, make a special exception in our case, keep the ranger station open and let our guide take us back out that very afternoon.

Peggy and I consulted our aching muscles, our blisters and our flagging stamina, overruled their complaints, and signed on for a second expedition tracking down chimpanzees.

That afternoon it rained harder than anybody has seen rain since Noah slammed the doors on the ark and floated away from his neighbors.

It rained so hard we had to walk with our heads down so we wouldn’t drown trying to breathe.

It rained for the entire five hours we scrambled up through jungle-covered mountains or skidded down the other side, clawing at vines and tree trunks to keep from being washed away.

It rained on the chimps, too. But chimps, not being fools, spent the afternoon crouching in hollow trees or sheltering under canopies of leaves.

It was still raining when the sun set and we sloshed and splashed our way back to the tent cabin where we spent the night, thinking about nothing so much as a hot shower to wash the excess water from our bodies.

Hot showers, as it turns out, aren’t something tent cabins are designed for. Ours did have a shower, but the shower was just connected to . . . it was raining too hard to see what the shower was connected to but my guess is there was a platform with a big, open tub that gathered and concentrated rainwater before letting it run downhill to the showerhead. Not to worry, the management said. We’ll send over some hot water.

The hot water arrived in a couple of big buckets carried by one of the employees. Whoever that guy was, balancing those buckets up what must have been a very slippery ladder in what was definitely one of the hardest, most unrelenting rains ever to fall on Planet Earth, he has a career in the Cirque du Soleil.

Thinking only kind thoughts about the gentleman who’d fetched the hot water, Peggy showered. Then I showered and toweled off and dug around in my bag for something less wet to wear. When we were finished we flopped on the bed, feeling warm and cozy and clammy and tired and blistered and . . . “Sir?” came from somewhere overhead. A plaintive sort of “Sir?” polite and loud enough to be heard over the rain. But barely. “Sir. Have you finished your showers yet?”

At supper our driver had some great news. We were just digging into the pumpkin soup in the mostly empty dining hall when he came and sat with us.

Something’s up, I thought. Democracy in social relationships hadn’t reached much of Sub-Saharan Africa. Usually it embarrasses an African for an American to try to eat with him. But here he was, joining us at our table. I thought he wanted soup and waved the waiter over.

He wasn’t interested in soup. What he was interested in was telling us how hard he’d been negotiating and how, since Peggy and I were the only people in living memory who’d ever missed seeing chimps, and we’d done it twice, the people in charge of such things were going to allow us to go out and try all over again.

The prospect of another day wandering the Kibale Forest looking for chimps sounds more thrilling at a distance than it did at the time. At the time we were shivering and tired, our muscles ached, our blisters hurt and our dry clothes – which had been damp when we pulled them from our bags – were wet from the walk to the dining hall. Still, it was something I knew in an intellectual sort of way I wanted to do.

It was something that Peggy, being more sensible than I, knew in a visceral sort of way that she didn’t want any part of. So, knowing Peggy the way I do, I answered first and we were on for tomorrow.

“I’m not going,” she said. “You can go if that’s what you you have to. I am definitely not going,” but I knew better. Peggy’s life is littered with adventures she’s not going on until the time comes to go and the adventure of the thing works its way into her and she can’t stand not going.

Seven o’clock the next morning the ground was so wet it couldn’t rain any more because there wasn’t any water left. It was all on the ground.

Four Russians were at the ranger station when we arrived. They’d come to see the chimps too. Russians, I thought. Russians are just the ticket. With Russians along it won’t be just Peggy and me. The chimps are bound to show themselves.

And they did. The guide took us down a mud road into the center of the forest and was just starting to go into his spiel about how-to-be-courteous-to-chimps when he interrupted himself.

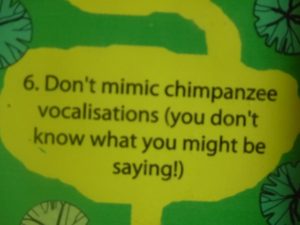

It’s always good manners to be courteous to chimpanzees

“Ooooh. Ooooh,” the guide said. “Chimps,” and darted into the trees with Peggy and me crashing along behind as close as we could keep up. Somewhere to the rear four Russians who didn’t know what all the dashing and crashing was about, worked their way carefully into the jungle.

We weren’t a hundred yards into the trees when a chimp dropped onto the ground close enough, almost, to touch.

A chimp landed at our feet

She was big, almost as big as a big male. Probably four-and-a-half feet, if she stood up, which she wasn’t doing. Just sitting on the ground looking at us out of limpid, brown eyes. A good hundred-and-fifty pounds, dark brown fur, almost black in the shadows, and muscles that could have ripped the arms off a cape buffalo. I was hoping she was one of those acclimated chimps who’ve become accustomed to humans. Whoever she was, she wasn’t Bonzo. And this wasn’t bedtime.

A dozen more chimps hooted in the trees and dropped to the ground. Some even glanced at us before wandering away.

There were more interesting things than us on the forest floor

Russians being Russians, they got up close and personal and began invading chimpanzee-space and I began to hope that chimps could tell the difference between ethnic groups of humans.

You only get an hour with chimpanzees, it’s built right into the system. Nobody wants chimps to become too acclimated to humans. That’s the sort of thing that can get a chimp killed if it thinks it’s become acclimated to a farmer who owns a banana tree. The chimps may have had a similar rule. “Don’t let those humans get too familiar or you’ll wind up in a circus working for peanuts.” They hung around for the hour then, on some signal that was lost on me, shot up the trees and swung off into the half-light.

The hour is up and he can go about his business

“Come on,” the guide said, and charged off through the forest behind them.

“Time to go,” the Russians said, and headed back to the road.

“Fair’s fair,” Peggy and I said. “This is our third time out here. We’re entitled to three hours,” and followed along behind the guide. Then spent another happy hour staring up into the trees watching chimps swinging and hooting.

Some cuddled babies or picked lice off one another. Others danced and napped. Or just blissed out.

Living the life arboreal

Or hung by one foot, then looped over to catch another branch, as joyous and free, it seemed to me, as dolphins.

Watching them made me homesick to be up there with them, as if I’d once been a chimp too, back before evolution trapped me in the wrong body.

No Comments