12 Dec Honolulu — The Last Pearl Harbor Day

Last Monday was Pearl Harbor Day and nobody came. That was the news from Honolulu: “No veterans attend today’s ceremony.” Pearl Harbor Day wasn’t even marked on my buddy, Don’s calendar, although Kwanza is. And Boxing Day.

2001 had been a different story. That was the year the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association held their sixtieth, and final, reunion. There wasn’t going to be a sixty-fifth. At the fifty-fifth, there’d been 12,000 members. By 2001, only 7500 were left. Nobody expected the next five years to be any kinder to these men.

This is our last chance, somebody at the History Channel must have thought, to get those guys on the record while we still can. So, the evening before Pearl Harbor Day, the Hospitality Room at the Ala Moana Hotel was filled with Survivors who’d agreed to interviews on live television. Don and I crashed the party.

The stories they told while waiting their chance at the cameras, were coarse, very funny and, by the sensitive lights of my generation, not particularly accommodating to the feelings of whomever the stories were about. As the evening wore on, and the mai tais went around, and each story topped the last, you couldn’t escape the feeling that so many of these men had shot down so many attacking planes that the war should have ended right there at Pearl Harbor, what with the catastrophe the raid had been for the Japanese.

A good portion of these guys were not, as my relatives in Georgia used to say, totally reconstructed. As word repeatedly down that there’d be another forty-five-minute delay in getting to the next interviewee, and mai tai’s continued to go around, everybody got louder and coarser and deeper into the spirit of the occasion. It was the kind of situation that would have gotten Don and me stern lectures as soon as our wives had us alone.

Their wives seemed used to it, though. Some even snapped pictures for future bargaining purposes as their eighty-something-year-old husbands climbed up on tables and mooned the room.

For most of these men, Pearl Harbor was only the beginning. They’d gone on to other fights – to places like Tarawa and Iwo, Guadalcanal and the Coral Sea. They showed Don and me photos of necklaces made from gold teeth. We learned that Japs kept POW’s alive in order to eat them. And that a lot of old feelings hadn’t dulled very much with the passage of the years.

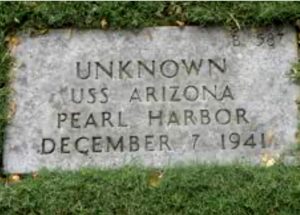

One unreconstructed old fellow mentioned he’d turned down a free trip to China to celebrate our joint victory over Japan because he refused to change planes in Tokyo. A tale was going around about a young Japanese couple who’d bowed and inquired of a grizzled old vet if he knew where the Arizona was. “Right the FUCK where you left it,” he’d shot back – to the hilarity and approval of every veteran within earshot. There were mutterings about a Japanese tourist shouting “banzai” at the Arizona Memorial.

I never heard for sure, but I have good reason to suspect that promises about live broadcasts had come to seem rash to the folks at the History Channel. At least one guy complained the next day that he’d talked for an hour, but only thirty-seconds of what he’d said actually showed up on television. From where I sat, that thirty seconds sounded generous.

At 7:55 the following morning I was in the lobby of the Ala Moana, surrounded by a sea of men in white “Pearl-Harbor-Survivor” caps waiting for buses to take us to the Punchbowl – the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Don, in the company of other Survivors, crashed a competing ceremony at the Arizona Memorial.

I’d made a point of being there at 7:55 because that was the exact moment, sixty years before, that the first bomb fell on Pearl Harbor. Nobody knew what had been planned in memory of the event but, at the very stroke of 7:55, the doors swung open and a green-and-white guidon came in, followed by people I couldn’t make out at the distance. The crowd parted and, arms swinging in a loose marching formation, whoever-they-were made their way around the far side of the lobby, then across the front until I got a good look at the green-and-white flag. It was the banner of a group of female athletes in town for the Honolulu Marathon. And the athletes were, there’s no polite way of putting this, they were Japanese. Young, slender, beautiful girls in Nikes, innocent as puppies, with no idea of what they were walking through.

It all felt so normal and right and, well . . . American, it was hard to see anything odd in the situation. And, as far as I could tell, nobody in the lobby, even the least reconstructed, treated it as anything other than the most normal and expected sort of thing.

I don’t know if this was intentional, but it was hard to hold anti-Japanese sentiments close to your heart at the Punchbowl. That’s because they sat us among the graves of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team – the heroic Japanese-American dead of the single most decorated unit in the entire war.

The Punchbowl is a lovely depression in the lush green of a shallow, volcanic crater on the outskirts of Honolulu. The headstones are the modern, maintenance-man-friendly variety

set right into the ground, so the place looks like an ancient garden lined with beautiful, twisted Chinese banyan trees

and rows of flag poles leading to a broad, ceremonial staircase rising to a Hindu-goddess looking figure who appears to be stepping through a wall of pale limestone.

The Punchbowl is as fitting a resting place as you could ever imagine.

But as for ceremonies – at least the ceremony that day – whoever organized it would have been better served just letting everybody sit in silence for a while, then loading us back onto the buses and shipping us home to the Ala Moana. Instead, the morning unfolded into a festival of political correctness. A salute to a war without an enemy. An honoring of heroes without the imagination to understand what those heroes had been forced to do.

A few days earlier, Don and I had taken the launch out to the Arizona Memorial. As we approached, it was arched over with a lovely, tropical rainbow that seemed metaphorical of something important.

I think something similar may have happened to the people who put the show together, because they all seemed to have rainbows on their mind. And unicorns. And gold, sparkly pixie dust.

Take a moment (right now would be a good time) to ask yourself whom you’d have appointed to give the convocation to 3,500 veterans of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Billy Graham? A military chaplain. An avuncular old cleric of indeterminate sectarianism? That kind of narrow, stereotypical thinking is why you weren’t invited to appoint anybody.

In the first place, they didn’t go with just one convocator. They called on three, separate, convocators. “Ah,” you say to yourself, “now I get it. One for the Protestants, one for the Catholics, one for the Jews. That would just about take care of everybody in the fleet, and on the air bases, and the marine base, and at Schofield Barracks that day”.

Those who did the appointing weren’t limited to the narrow confines of your outmoded Western faiths. The first inspirational religious person was a by-God Hawai’ian pagan priest singing ancient chants. The second was a Buddhist who kind of buzzed his chant. And the third? The third was a genuine imam decked out in white imam robes who actually gave a comprehensible little sermon in English. And, even more comprehensible, he spoke about toleration, a virtue he’d surely wanted to plant in American souls for the three months since people of his own faith had displayed their tolerance by blowing the bejabbers out of the World Trade Center.

Picturesque as it all was, I could have done with something from our culture – a few words from Isaiah, perhaps, about nations not lifting up their swords against nations. Or from our own pre-Christian heritage – a fourth convocator with bear-skin robes, a giant ax and a huge, red beard; a tradition of gallant men and warrior gods, and a place where the two meet every morning to fight, and to drink and swap lies in the evening. A tradition that bridged the chasm between the still-living, and their comrades laid around us who were already drinking and singing, swapping lies and fighting and raising hell, and rising to do it all over again in an endless celebration of manhood and courage and good fellowship.

The Heavens seemed to have a better understanding of what the ceremonies were about than the people in charge, and they weren’t having any foolishness about rainbows. To the west, the sky was the bright, translucent blue that makes you feel like you can see all the way to throne of God. To the east, it was the dark, roiling chaos of the world without form where you could see God, Himself, moving upon the face of the waters. The line between the two ran right up the main axis of the cemetery – from the tall flagpole, through the graves of men who’d already died, along the aisle separating the seats of the still living, across the dais, and up the ceremonial stairs to the strange, monumental sculpture and the hills beyond.

Sometimes the line would waiver east, scorching sun onto our necks, then west, casting us in shadow and swirling winds while we braced for a squall. A celestial struggle between skin cancer and cold, wet, matted aloha shirts.

On that island on that day, set among the graves of the no-longer living, beneath the endless Pacific sky, clouds roiling on one side, sun and peace on the other, the infinite was so close you had to look at your feet – or pay attention to the speakers – to keep it at bay.

General Richard B Myers was the lead-off speaker, and chairman of the Joint Chiefs in America’s brand-new war. And that very day was the day our guys kicked the Taliban out of Kandahar. He had the chance to be interesting.

He blew it, and the program went downhill from there, through a colorless assortment of politicians seeking to warm themselves in reflected glory: Medal of Honor winners who were reflecting glory like mad; family members of World Trade Center victims; NYC firemen; representatives of military associations; and Hugh O’Brian . . . who’d achieved anonymity as a marine during the Second World War but, in later life, shimmered with glory as a pretend Wyatt Earp.

No Comments