31 May Kalahari Desert 1 — World’s Oldest Culture

Bushmen have lived in Botswana for at least seventy-five thousand years. They are keepers of the genes, and the ways, and the stories, of those who stayed behind when our ancestors wandered out of Africa to see what was in the rest of the world. Now they’re pretty much limited to the Kgalagadi Desert, which nobody else wants, and little pockets scattered here and there across the rest of their ancient homeland: Namibia. Angola. Botswana. Zambia. Mozambique. South Africa. Swaziland . . . where nobody else wants them.

Shadrach was a River Bushman who grew up in the endless marshes of the Okavango Desert. Sometimes he’d pick up money leading rich people on game walks at one of the thousand-dollar-a-night lodges. Or team up with a man named Jeff, a sergeant from the old South African apartheid army, and guide people like Peggy and me in the Delta. One night out near Ivory camp when everyone else had gone into their tents, he told me where the stars came from.

“In early days, a great hunter became lost in the Kgalagadi.” Wreathed in smoke from the dying fire and surrounded by the sounds of an African night, he might have been one of his ancestors sitting in the same place, on the same leadwood log, passing along the same story.

“Day after day the hunter tried to find his way home, but every path he took led farther into the desert. One night, he lay down beside a camelthorn tree and prayed to his ancestors for help. At that moment his wife knew he was lost and built a huge fire to light the way.” Shadrach gestured at the tent a few meters back in the shadows where Peggy was waiting for me. “That one would build a fire for you, I think.”

“Sparks jumped so high the hunter could see them all the way from the camelthorn tree. He knew his wife was calling, and he stood and started walking. Days later, he found his way home.”

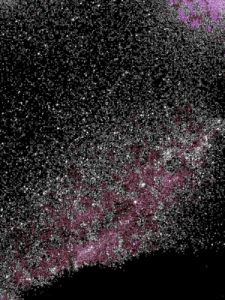

Overhead, the night was alive with sparks from that long-ago fire: the Milky Way, the Southern constellations and those familiar to us in the North, nebulae, and the Cross, and the Magellanic Clouds

still lighting the sky, just as they had when his mother passed the story along to him, and her mother, to her. And hers . . . or, perhaps, their fathers.

Three thousand generations of his people, of parents and children, of old men and old women drawing close around dying campfires, sharing food, listening to the sounds of the night, gazing up at the sparks set in the heavens and knowing they were home. That story, the story of the night sky, must be one of the oldest stories in the world.

An old British colonial officer who’d stayed in Botswana after independence, told me a story, too. That in the early Sixties, he’d been driving along the northern edge of the protectorate when he came across a group of Boers with a dead Bushman strapped to the hood of their car. They had been hunting men.

That man had been a member of the oldest cultural group on the planet. And we have no good name for them: Hottentots. Bushmen. San. Khoisan. Khoe-Khoe, they’re all derogatory. The names that aren’t, they’re the ones they call themselves in the four different language groups, not languages, language groups, that nobody else on the planet shares, names that are so filled with clicks the rest of us can’t even pronounce them. Since there’s nothing you can actually call them that doesn’t insult somebody, you might as well call them what you want. Most people I know refer to them as San, and they don’t mean anything bad by it. I prefer Bushmen because Bushman sounds descriptive to me: the people who make a living in the bush. Nobody else can do that. Or trace their pedigree back so far.

Up in Tsodilo Hills, Peg and I met a lady squatting in the shade of a small museum. She was breaking ostrich shells into little pieces. Some were black from fire, some were a rich brown from less fire, others were eggshell white.

We watched as she strung them into jewelry: complex, twisting patterns spiraling through three dimensions, resonant with the blacks and tans and eggshell-whites. I bought a necklace for Peggy.

A future 35,000 year old necklace

Fragments of ostrich shell were inside the museum, as well: black and tan and white fragments the lady could have made just that morning. They came from a nearby cave and were thirty-five thousand years old, making the necklace Peggy was wearing part of a still-living tradition passed from mother to daughter to granddaughter from a time as far away from the cave paintings at Lascaux as those paintings are from us.

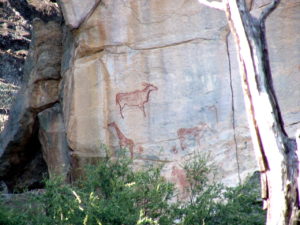

Tsodilo Hills contains the largest concentration of rock art in the world

scattered across thorn-covered, almost inaccessible slopes.

Curving around the bottom of the hills are dry riverbeds which Bushmen say are marks left by the giant python that created their ancestors. Inside the cave is a boulder fashioned in the shape of the python. Scattered around the python were thirteen-thousand sacrificial objects. Some were seventy-thousand years old, the oldest artwork ever discovered. As much older than the oldest ostrich-shell beads as those beads are from us. Four times the age of Lascaux. Millennia before our people had even left Africa, that’s how long the ancestor of the Bushmen strapped across the hood of that car had been living on that land.

No Comments