07 Jun Kalahari Desert 2 — The Relocation

One weekend Peggy and I were driving along a dirt track in the Central Kgalagadi when we encountered a family of Bushmen, a dozen maybe, carrying bundles and leading a pack horse deeper into the desert. They glanced at us, to be sure we weren’t the army, I think, then kept on walking. It was against the law to be a Bushmen on your ancestral lands.

People whose families had lived in the Kgalagadi for three thousand generations. Parents and children, old men and old women drawing close around campfires, sharing food, telling stories, listening to the sounds of the night and gazing up at the sparks set in the heavens, had been forced off their land at gunpoint.

A couple of years earlier they’d won a lawsuit ordering Botswana to let them return. The country isn’t a dictatorship, so the government had to comply, but complying didn’t mean very much by the time they got through parsing the decision. They decreed that the ruling didn’t apply to Bushmen in general, only to the handful specifically named in the lawsuit.

The president didn’t like having to deal with Bushmen and he referred to the ones who’d won the right to go home as, “primitive, Stone Age creatures.” Then he sent the army in ahead of them to pour concrete into the boreholes Peace Corps volunteers had provided in the mid-Sixties. “You want to preserve your way of life? Then go live like your ancestors.” And, of course, nobody could. Not after a generation-and-a-half of getting their water from boreholes meant for cattle.

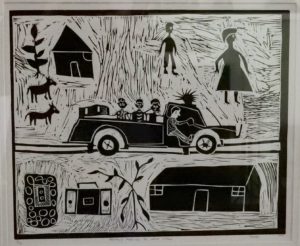

On her last day at work, Peggy’s staff gave her a going-away gift, a linoleum-block print called The Relocation. It shows a pickup truck, I think, filled with children. A traditional house is on the far side of the road, along with a couple of animals that might be jackals, and a woman in a long, missionary dress. It’s a picture of the day the army rounded up the Bushmen and expelled them from the Kgalagadi.

The kids in the back of the pickup, probably including the one who made the print, are staring with wide, round eyes at the new world they’re being forced into. A modern house. What look to me like a light socket and a boom box. A plant they’d be expected to tend. It reminds me, when I look at it now, of Picasso’s Guernica, awkward and odd looking and as heartfelt and evocative as anything ever put on canvas.

Or, in the case of The Relocation, on print paper, by a kid who will never have the opportunity to become his own Picasso because a primitive, Stone Age creature is all his countrymen will ever see in him.

If you ask the government what that’s all about, moving people off their land, they’ll put a good face on it. “Bushmen are citizens, too. Just like the rest of us.” they’ll tell you. “Bushmen deserve the same services we all get. But it’s hard to provide education or medical care to people wandering around in the Kgalagadi. Moving them into settlements was for their own good.”

There were other reasons, reasons people trot out if you didn’t quite buy the thing about how kicking them off their ancestral lands being for their own good.

“It never really was their land. It’s the country’s land. The Kgalagadi belongs to all of us.”

“We did it for the animals,” people way if you’re a foreigner. “In the villages, they don’t have to kill animals in order to eat. They have cows, like everybody else.” Foreigners are all about protecting animals.

“It’s a shame,” they tell each other when no foreigners are around, “but what choice did we have? They were in the way of progress.” Progress is diamonds, and the Kgalagadi is where the diamonds are.

“Diamonds are for the Bushmen, too,” they’ll explain if a foreigner overhears the thing about the diamonds.

Even rounded up and in artificial settlements, there weren’t enough children in one place to set up decent schools. So the government put them in a boarding school. The school is in a bleak, artificial village called New Xade where the kids are as foreign to each other as they would be to children from the Australian Outback. And the languages they speak are as different as English is from Macedonian. Or Sanskrit from Celtic. The only thing that ties the languages together, besides being unimaginably ancient, is that they all have clicks. Which means the teachers can’t pronounce the students’ names, so they took away the only thing the children still owned, and assigned them Setswana names.

The place is a rambling, one-story brick affair with dorms and showers, a cafeteria and classrooms, even a playing field. In Botswana, there’s always money to build things. The country throws a ceremonial opening, politicians strut and take credit, people shout “Pula” and, sometimes, there’s an operating budget. Sometimes. Other times, clinics never operate because they never receive medical supplies. Maintenance is even farther down the list, and a school for the children of Bushmen hidden away in the Central Kgalagadi is so far down the list it’s fallen right off the bottom.

Peggy and I arrived on a Saturday morning. The showers weren’t working, the toilets were plugged, glass was busted out of the windows so that big, stinging Kgalagadi insects swarmed the children at night, and there were no grownups.

None.

Not an administrator.

Nor a teacher or a coach.

Not a janitor nor a groundskeeper.

Nor a nurse, if one of the kids got hurt, nor staff to keep them from getting hurt, nor cooks to feed them. The grownups had all split for D’Kar or Ghanzi to spend the weekend with their own kind. Some would come back on Monday. Some on Tuesday. Some would probably stay on through to the following weekend. It made you worry about what might happen to the girls and the smaller boys. It made you worry what was going to become of the older boys, too.

There were kids wandering about the playing field, a couple of girls squatting on the ground, tossing a stone into the air, then quickly picking other stones out of a depression in the sand as, I imagined, their mothers and grandmothers had been doing before our people wandered out of Africa to see what was in the rest of the world.

Knots of boys ran around, not learning how to hunt or track or find water because there was no one to show them. Nor how to read or do sums, because there was no one to show them that, either. Nor how to respect themselves or their elders, because there were no elders to learn from.

That was it, right there on that dusty playing field. The place where the longest, unbroken human culture in the world came to an end. Where 75,000 years of tradition, of knowledge passed down from grandparent to grandchild to grandchild was silenced. Where a living heritage four times as old as the cave paintings at Lascaux was lost forever. In our lifetimes.

“They’re San. Hottentots. Khoe-Khoe. Khoisan. Bushmen. It’s not like they’re people, not really, not like you and I are people. A Bushman can run all day in the heat chasing down a kudu. No human could do that.”

“They smell bad, too.”

“And they use witchcraft, just look at their dances.”

Those are easy words to put out of your mind when you’re as fond of the people saying them as I am of black Batswana. But when you go out to New Xade and see what those words mean. When you meet those children dumped into a slum with no one to fix the plumbing, no one to feed them, no nurses or housemothers or teachers, no one to show them how to be adults, no one to protect them from insects, or marauding animals, or each other, no one to teach them the ways of the modern world . . . or the hunting and tracking, the ancient dances and stories, of their own people . . . that was the only time during our entire stay in Botswana that I looked at the country I’d grown to love, and wanted to go home.

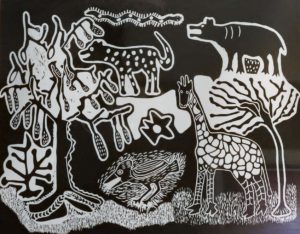

Bushmen hadn’t just been in the Kgalagadi, of course. They’d lived all over Southern Africa before blacks pushed down from the north, and whites shoved up from the south. A group of kids from the settlements got invited up to the Okavango Delta to see for themselves some of the land that had been theirs. They took along sketchbooks so they could remember what they saw. When they got back to the settlements they made block prints from the sketches and sent them to Gaborone for an art show.

It was the same show where Peggy’s staff bought The Relocation, and the saddest exhibition I ever went to. We bought a print of a sausage tree, the huge, water-loving tree we’d almost camped beneath on a riverbank in the Okavango Delta before we discovered the three-pound, wood-hard sausages that came screaming down in the middle of the night. The kid was just as amazed by the tree as we’d been, and built the picture around it, filling it with animals and the spaces nearby with a snake, a bird, wetland plants he’d probably never see again.

Sometimes, now, I think of the African night alive with sounds, and the sky a blaze of stars. And of a River Bushman wreathed in smoke from a dying fire, passing down the story of the hunter who’d lost his way and the sparks from the fire that led him home. And of the thousands of generations of his people stretching deeper into time than any of us can possibly comprehend, drawing close to their own fires, gazing up at those same sparks and knowing that they were home.

And of the kid who made the print that hangs in my study, gazing into the same sky remembering his people, and what those sparks meant to them, and imagining that, someday, he might find his way home, too, back to the parts of Africa we both glimpsed so briefly and came to love.

And knowing that, in my case at least, I never will. That for me, Africa is over.

__________________

Next, we crash a dance festival where Bushmen come from all over southern Africa to reclaim their heritage.

No Comments