15 May Cayman Trench — Enraptures of the Deep

Having preciously descended to a thousand feet with Karl Stanley and his homemade submarine, two-thousand feet beckoned and we decided to go again.

Karl, if you know your who’s whoms in the world of backyard submarine builders, was the kid who managed the seemingly impossible feat of getting expelled from reform school . . . only to wind up in a mental institution for his troubles. From which, three months later, he convinced a panel of doctors he wasn’t crazy, just suffering from something called “defiance-of-authority” syndrome. Sometime later, he was arrested for detonating fireworks from the roof a police station. By any measure, Karl was not the kind of kid anybody would give a submarine to.

In his senior year he took his first dive off St Petersburg and, because the American Bureau of Shipping wasn’t about to certify a homemade submarine, moved to the island of Roatan off Honduras where regulators aren’t such fussbudgets.

He began taking customers down to 725 feet, got into fights with the neighbors, the vice-mayor, the Honduran government, and began work on a second, deeper-diving submarine. In 2004 he launched the Idabel, and began selling trips as deep as 2,000 feet. Peggy and I bought one because we wanted to visit a Lophelia reef.

Lophelia reefs are something new under the sun. Or would be if the sun ever reached them. They occur in cold, dark water from 1500 to 10,000 feet, and nobody had heard of them until about six years ago.

Lophelia coral is exceedingly slow growing, an inch every ten years or so, some of the reefs are enormous, and there are a lot of them. They ring Greenland, the islands in Hudson’s Bay, and run down the East Coast at least as far as Honduras. On the other side of the Atlantic, they extend from the waters north of Norway to Angola. People who keep track of such things think there’s more coral in Lophelia reefs than in all the warm-water reefs of the world, and Peg and I wanted to go see.

Homemade or not, the Idabel is one beautiful, bright-yellow piece of machinery.

We slid down a narrow hatch, pretzled around a right-angle turn and onto a narrow bench behind a five-inch thick Plexiglas bubble.

Karl cruised a few-hundred-yards into the bay, pulled the plug and, within minutes, we were deeper than we’d ever been with SCUBA tanks.

Then deeper than any diver had ever been, period.

The water turned dark as we left the warm, tropical ocean sparkling with familiar fish and corals and reef creatures, and entered the mesopelagic where seasons never change, sunlight never falls, and there’s no photosynthesis to support life.

Karl switched the floodlights on.

Then off, and the view filled with lights

from tiny creatures flashing back at us.

Just before hitting bottom the Idabel levelled off.

We were at 2,000 feet.

A lone fish was swimming around but the real action was below ground, mollusks buried in holes in the sand. I’d always supposed that “the ocean is a desert with its life underground” was some kind of veiled drug reference, but now I was starting to think the song might be onto something.

After a while we encountered a sea urchin

as big as a cantaloupe.

It was hard to figure what such a thing could eat. Without sunlight there’s no algae. And without rocks, there’s nothing for barnacles to stick to. Maybe it bored into the sand for shellfish.

It was even harder to figure what a lobster might eat, but there one was,

pale like something you’d find under a board the backyard. And, judging from the way it reared and challenged the Idabel, the apex predator of the ocean bottom.

A few-hundred yards further along we started seeing things we wouldn’t have seen in shallower water. A ratfish

with a long, pointed, rodent-like tail: one more predator with nothing obvious to prey upon. It was as if we were in the Serengeti seeing lions and cheetahs and leopards, but no zebra or wildebeest or impala.

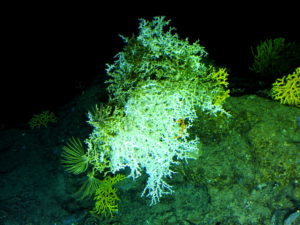

We came across a glass sponge

attached to a rock outcropping. Glass sponges are beautiful and intricate, and really are glass. Or at least, glassy, because they’re laced with silicon. And they live for 15,000 years. This one may have been in that same spot, anchored to that same rock, while mile-thick sheets of ice covered Europe. While Peg’s and my ancestors were painting extinct animals on caves in Spain. While the very first humans were making their way into North America. It’s cold where they live, with no light and not much food, and life can move slowly.

We could feel the cold ourselves, creeping through the Idabel. The water temperature dropped into the fifties, moisture condensed inside the hull and, since part of the deal was that we left our shoes on the dock, our feet were wet.

A dinner plate jellyfish moseyed by

looking for something to eat. Dinner Plates are the only jellyfish that actively hunt instead of just hoping to drift into something.

In time, the sand gave way to an oasis of life. A tinselfish

flashed in the lights from the Idabel and, behind it, Lophelia coral.

Intricate, delicate, exceedingly old, and patrolled by a spidery-looking crab.

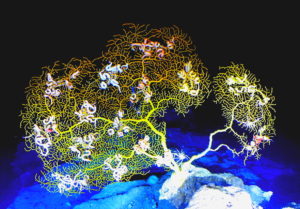

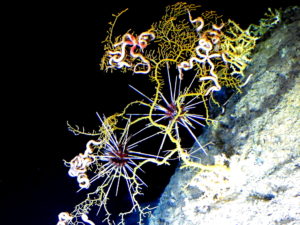

Gorgonian sea fans were laced in a symbiotic relationship with wriggling, wormy-looking snake stars

in a tableau more beautiful than any Japanese ikebana flower arrangement. Shimmering under the lights, the dark ocean behind, the sight took my breath away. As did the urchins and snake stars on another gorgonian

As did the urchins and snake stars on another gorgonian

Sea lilies, ancient animals whose lineage extends all the way to the mid-Cambrian, were arrayed on a glass sponge.

The images from my camera pale beside those in my memory. And none of them compare to the physicality, the sheer astonishment of sitting inches away, watching through a Plexiglas window.

Minutes later. Or, maybe, a couple of hours, we were working our way up the side of a cliff when Karl homed in on a slit snail,

a creature from the Upper Cretaceous that survives by being difficult to prey upon and monumentally unpalatable. The slits let it breathe without coming out of the shell, its body is laced with silica from eating glass sponges, and it spews a foul, milky substance when disturbed.

Also, slit-snail shells go for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars on the rare shell marker. Which made me suspect that Karl didn’t just happen on this snail. He knew exactly where to find it.

I’d never previously considered that owning your own submarine might have commercial possibilities other than just taking paying customers to the bottom of the ocean, but that shell started me thinking. And wondering what, exactly, was the legality of catching deep-sea seashells. And how you’d go about it. It wasn’t like you could just reach out and grab them.

After the dive, Peg and I were heading back to our hotel when came across a British expat who knew we’d been on the Idabel. “How’d it go?” he asked.

Well, it had been pretty extraordinary. There wasn’t a lot more to say, so I asked the obvious question. “You ever go down with Karl?”

“Once,” he said. “He needed me for ballast.”

“Ballast?”

“Yeah, he wanted somebody to sit up front.”

“What was he up to.?”

“He had a dip net attached to the Idabel and and he’d motor up to these seashells and try to catch them. He’d ease forward to get the net in position, miss, back off and try again. It was hilarious, like watching a video game.”

No Comments