24 Apr Marquesas Islands — Dancing in Eden

Genesis is a bit vague about where the Garden was located, but being furnished with every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food, along with perfect weather and animals that don’t want to eat you, it sounded like the kind of place that doesn’t really exist. Still, searching for it is how Peggy and I wound up on Fiji, where we met a Swiss lady who told us where to look. The Marquesas Islands.

She’d spent her years wandering the Pacific and was impossibly frail. The Old Woman of the Sea is how I remember her. An aging water sprite. The Keeper of the Mysteries of an endless ocean.

Once, when she was working at a research station in the Galapagos, Marlon Brando happened by in his yacht. She’d bid aloha to the giant tortoises and marine iguanas and sailed with him to his private island . . . which she discovered wasn’t as private as advertised when Mrs Brando turned out to be in residence.

“Every four years,” she told us, “Polynesians from all over the Pacific hold a dance festival in the Marquesas. It’s not a show,” she warned us, “the islanders dance for themselves.” But outsiders were allowed to watch. If they could figure out how to get there.

Which isn’t easy because the Marquesas are some of the most isolated places on earth. Tahiti is the nearest anything, and it’s almost a thousand miles away. There aren’t any commercial flights, at least not that Kayak or Orbitz or CheapOair know about. Which reduced us to dealing with travel agents.

But they didn’t know any more than the booking sites. The fact is, the ones we talked to didn’t even seem to know where the Marquesas are. Or, for that matter, that they’re Islands in French Polynesia. In the end, I found a posting from somebody who’d attended the festival four years earlier . . . by freighter.

The freighter was the Aranuii III, a Chinese-owned vessel out of Pape’ete which made the circuit of the islands . . . Nuku-Hiva; Hua Pou; Hiva Oa; Fatu-Hiva; the other side of Hiva Oa; Ua-Huka; Nuku Hiva again; and, on the return, Bora Bora. Round and round she went, every two weeks bringing lightbulbs and beer, cornmeal and motor oil and just about everything else the islanders needed from the modern world. Given the fact she was the third Aranuii, this must have been going on for a long time.

Imagining all those Aranuiis made me think of Indiana Jones off the coast of Portugal, sloshing across the deck in high seas trying to retrieve the Cross of Coronado before the ship blew up.

And Terry and the Pirates.

And Faye Wray on the Venture, caught in fog in the waters off Kong Island.

The next morning, I alerted my buddy Sam. And he and his gal, Charlotte, and Peg and I, booked the last two cabins on the Aranuii III.

Whatever that ship was really like, or the I or the II for that matter, we never discovered because, by the time we boarded, she’d been supplanted by the Aranuii V.

The number IV being very unlucky, at least if you’re Chinese, the owners skipped right to V when they designated her replacement. Also, they’d noticed there was money in hauling people around the Marquesas and turned the entire back half of V into a cruise ship kitted out with lounges and a dining room and a pool and space for genuine Marquesans to sleep under the stars as they transited from island to island. The front half was still a working freighter with cranes and containers and deck cargo.

The crew was Marquesan, and famously laid back . . . at least they’d been on the III. That’s what the experienced passengers said. But not so much on the V, not on our trip. This being her maiden voyage the owner and his family came along, which led to good service in the dining room, but made the crew nervous and not as inclined to joking around and playfulness as previous passengers had come to expect.

The dance festival was on Hiva-Oa, and the entire island, it felt like, met us on the dock

arrayed in their finest banana-leaf skirts and leis. They swayed and danced and sang and drummed us welcome, looking like they’d been conjured from the collective Western imagination of what landing on a Polynesian island was supposed to look like. A lot of that . . . maybe most of it . . . had to do with the presence of the Chinese family. And that the arrival of any Aranuii is a very big deal in the Marquesas.

The ancient Swiss lady materialized on the dock as if she’d sprung from the island, draped in bright cloth and looking even older and more frail and more filled with life than on Fiji.

Somewhere during her travels she’d begun forging her yellow card and, by the time we met her, had become one of the world’s oldest surviving anti-vaxxers. Which may have had something to do with her frailty because she’d also become host to the entire alphabet of Hepatitis: A, B and C.

Ashore, the Marquesas look exactly like you think islands in the South Pacific look. They’re misty and craggy, the air is filled with strange birds, and a single glance made me wonder if the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil might be in a nearby valley, and the Tree of Life just on over the mountain.

Paul Gaugin was there . . . buried near the house he built after he’d run into trouble getting ladies on Tahiti to pose for him. I never got the full story on that, but it may have something to do with the church. In any event, he migrated to Hiva Oa and, among a lot of other art, produced a carving of the local bishop

that looks remarkably like the devil. He named it “Father Lechery” and turned his home into a party house for islanders to drink and sing the night away.

The dance festival took place on traditional platforms: rectangular grassy patches surrounded by low stone walls that could have been mistaken for the playing fields behind grammar schools at home . . . or Aztec ball courts without the stone hoops. The main one, the one in the lower part of the island,

had wooden shelters for spectators.

The sight of those long, thatched roofs backed against the forest with mountain and sky behind made me wonder why Gaugin wanted to limit himself to such closed-in subjects.

The dancers didn’t turn out to be from every island in Polynesia, but they did come from every inhabited island in the Marquesas. And from Easter Island. And Hawaii. And New Zealand . . . which pretty much covered the Polynesian dances I know about.

The young men were stomping, rhythmic, yelling, wild, graceful, noisy, powerful, noble-looking and arrogant

in the pride of their manhood.

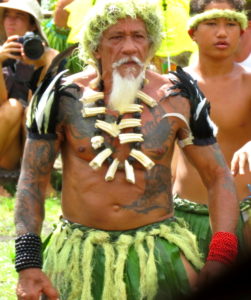

Or white-haired and resplendent with tattoos, because the ancient tattoos were being revived, too.

Women danced, as well. Lines of women. Ranks of women swaying and chanting and turning. Sometimes fierce. Sometimes lithe and liquid and flowing and sexual. Women with flowers and greenery in their hair and covering the parts of themselves that most identified them as women.

Women filled with life and promise.

Women dancing for themselves. Dancing for their husbands and children. For lovers and ancestors and for the future they carried in their bellies. All the dancers sons and daughters of people who’d come to these islands a thousand years before we did.

Or, at least most of them. Because a few were blonde

tracing their lineage to sailors who’d dropped by a hundred-and-fifty years earlier, two-hundred years.

Gaugin’s model for Jeune fille was one of these,

the red-headed daughter of a chief on a neighboring island.

In the highlands, other dances took place on other platforms, platforms half-hidden by jungle. Platforms that seemed less tended. Wilder. More remote, as if we’d hiked halfway back to the time before missionaries.

Platforms still watched over by the gods their ancestors had danced for.

It was hard to decipher what all this meant to the islanders. Was it just a few days every four years that they put on the heritage they never really get to live?

Was it like Southerners, patriotic Americans, priding themselves on the heroism of their ancestors in the Civil war?

Were they taking the first step to becoming the people they would have been if Jesus and smallpox had never entered their paradise?

It was hard to know, because we all carry other images of the South Pacific that are just as powerful. And on a Sunday, we encountered them, too. A graceful stone church

set against mountains and a tropical sky, not that different in feeling from the dance platforms. And from inside, Christian hymns spilling into the tropical air. Some of the loveliest, the most touching, the most inspiring praise to Jesus I ever heard.

No Comments