11 Oct Truk Atoll — Diving Truk Lagoon

Of all the places I’d imagined drunken sailors, the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Second World War was not among them. But that was before Peg and I got a look at the sake bottles strewn along the bottom of Truk Lagoon.

Truk, now sailing under the moniker, Chu’uk, is one of the biggest atolls in the Pacific which, in late 1943, made it an ideal anchorage for a large part of the Japanese fleet. The surrounding reefs protected ships from American submarines. The islands provided bases for air cover. The location gave the Japanese a forward supply base for their ships and soldiers farther to the east.

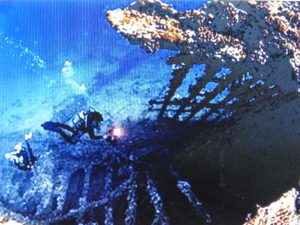

And all those reefs and islands blocked any possibility of escape the morning of Feb 17, 1944, when America launched Operation Hail Stone, 560 warplanes appeared overhead, and forty Imperial Japanese ships descended to the bottom.

Which makes Truk Lagoon one of the primo dive sites in the world for the historically minded, if a bit inconvenient to get to.

In fact, it’s damned inconvenient. You have to go to Honolulu, then take the Island Hopper to Majuro. From there you fly to Kwajalein where you can’t even get off the plane because Kwajalein is a military base. After Kwajalein, it’s on to Kosrae, then to Pohnpei and, finally, Truk. The Island Hopper flies three days a week, and the trip takes so long, and the islands are so remote, that the plane carries a mechanic, spare parts, and four pilots. Because the landing strips are short, fire trucks wait beside the runways to cool overheated brakes..

One of the things that made the raid on Truk so successful was the fact that we’d broken the Japanese naval code. The history books don’t talk much about this, at least no book I ever read, but one of the things that made the raid less successful than it could have been was that the Japanese had broken our codes, as well. Which meant they knew Hail Stone was coming and, three days earlier, moved their warships to Palau. So today, when you dive Truk Lagoon, you’re diving among support vessels. That doesn’t sound as interesting as warships until you go down and see for yourself.

Our first dive was on a sub tender, the Heian Maru. One compartment held periscopes, and another Type 93 Long Lance torpedoes,

the most advanced torpedoes in the world at the time. Whoever sent the Heian Maru to the bottom may have saved scores of American lives.

Next was a coastal freighter, the Gosei Maru. We entered a hundred-and-five feet down through a hole blown in the stern, then worked our way up through the wreck to the captain’s bathroom of all places. Dinner plates lay about and sake bottles. And beautiful corals. This is where we first began to notice the sea life that had taken over these ships.

The Nippo Maru held gas masks,

a truck frame, and what looked to me like a Type 95 Ha-Go light tank

. . . which, when you think about it, was quite a load for a ship billed as an auxiliary water carrier.

The Sankisan Maru, a passenger freighter, contained the Japanese equivalent of a jeep

along with machinegun bullets,

and, scattered around the stern gun, casings from five-inch shells showing that somebody had put up a fight.

The Fujiyama Maru held five Zero fighter planes, disassembled with wings stacked to one side so the planes could fit into the hold.

During a surface break between dives, we snorkeled a fully-assembled Zero that had settled onto its back in shallow water off the end of one of the airstrips. The tail was encrusted with coral, so it was hard to tell about the tail, but there wasn’t any obvious battle damage on the rest of the plane. All that had happened, so the story went, was that the pilot had missed his mark while landing.

A Betty bomber lay at sixty-five feet with the front end missing. We swam around examining the tail and the wings . . . attached by what looked like tens of thousands of rivets. Then swam inside, working our way past seats and fallen gear, twisted wiring, broken glass, broken metal and out the front. But what I remember most are the rivets, rivets still holding true after all those years, after all that plane had gone through.

I’ve never associated the Japanese in that war with anything having to do with love, but you can’t look at that kind of workmanship and not see the love that went into it. And think about the women who built that plane. I imagined them in kimonos although they were probably dressed more like Rosie. Women standing on ladders or crouched in narrow spaces, row after row of women standing and crouching the same way their sisters around the world were standing and crouching just then . . . German and Soviet, American and British . . . building machines for their men who’d gone off to war . . . a war that the lovers and husbands, the brothers and fathers of the women who built that particular plane didn’t have a snowball’s chance of winning. Or, in lots of cases, even coming home from.

In other ships we saw motorcycles,

bicycles, oil drums, a ship’s telegraph

that the captain must have used to signal full speed ahead when Americans appeared overhead.

There were food tins and sake bottles and the other the detritus that living people leave behind.

There were delicate, porcelain plates that, somehow, had managed to survive the explosions, the fires and sinkings; and more sake bottles.

Many, many more sake bottles. Sake bottles spilling from holds. Sake bottles scattered across decks. Sake bottles half-buried in the sand. Sake bottles still in their original boxes.

At first I imagined the bottles were of more recent vintage than the ships. That relatives of the sailors, veterans’ groups, politicians, patriotic Japanese and ordinary tourists had come to Truk, rented boats, motored over the wrecks, dropped wreaths into the sea, toasted the gallantry of their fallen countrymen and flung in the bottles the way we would have. But nobody I spoke to had any memory of Japanese ever doing such a thing.

On the bridge of the Shinkoku Maru we saw something even more unimaginable to Americans who, two generations after the fact, are still combing the jungles of Vietnam for the remains of fallen airmen. Human bones displayed on the chart table.

There’s an ethic about this sort of thing among wreck divers. Sunken ships are the only memorials lost sailors get. You don’t disturb the people in them, and I don’t know what that diver had in mind. I hope it was respect, that he laid out those bones carefully to honor the man they’d been, not just to pose them for photographs. But, who knows? Nearby, clown fish played around a shocking pink anemone.

Our final dive was a freighter, the Yamigiri Maru, sitting upright on its keel. Below decks a steamroller waited in the same hold as eighteen-inch artillery shells. Swimming in there makes you wonder how well that steamroller had been secured, and what might have happened if it had broken loose in rough seas. For that matter, it makes you wonder how long explosives remain viable underwater, and what would happen if the Yamigiri Maru shifted while you were inside. But that isn’t what Peg and I remember most about that ship. What we remember most is swimming slowly in sunlit water along the top deck.

The Yamigiri Maru had not been beautiful. She’d been one more workaday bottom, rusty probably, and stained like all the others from years at sea with only basic, wartime maintenance. Not fast or sleek when she settled below the waves, just belching black smoke into the tropical morning, and oil into the lagoon. Now, after three-quarters of a century, nature has turned her into a lovely garden. Sea fans and corals and anemones

in all the colors of the flowers that blossom onshore.

Fish sparkle in the dappled light. Inquisitive octopi work their way across a deck last trod by terrified, screaming, injured, burning humans. That kind of beauty, in that kind of place . . . within the living memory of men who’d actually been there during that ship’s final moments . . . comes as close in my mind to the miraculous as any miracle will ever come.

No Comments