22 Jan In the Wake of John Wesley Powell

The Grand Canyon has had a reputation for treacherous white-water rafting since John Wesley Powell’s expedition barely made it out alive. You can see why they had trouble.

Rubber rafts hadn’t been invented in 1869 so they used Boston whalers, which are long, narrow, hard to steer and exactly the wrong kind of boat. And, because the oarsmen faced the wrong way, they had to run the river backwards. None of which was made easier by the fact that no American had ever been down there before, and nobody knew what to expect. Also Powell only had one arm, having left the other one at Shiloh.

By modern standards, the Colorado isn’t nearly as scary as its reputation. It’s got a few class IV and Class V’s, but they’re spread over 277 miles. On 8-person rafts ballasted with food and camping gear, running the Canyon feels more like scooting along in an open-top tour bus than a knuckle-biting whitewater adventure.

.

The rapids are created by debris flows that wash huge boulders down side canyons and into the river. For most of geological time, annual floods rolled the boulders into more hydraulic arrangements and smoothed out the water. But not anymore. With the Glen Canyon Dam upstream, floods don’t flood, boulders sit where they’re dumped, rapids become rapider, and the Colorado grows wilder and more scenic.

Peggy and I went in April because, in April, the Park Service only allows one outfitter to run one trip per day. Which means no waiting your turn at rapids and no fighting over who gets to pitch who’s tent on which sandbar. It also means that daytime temperatures are in the eighties, not the hundred-and-twenties. Which is a plus, seeing as how going down the Colorado is more like a hiking trip interspersed with bouts of rock climbing, bouldering, and the occasional light spelunking, than a rafting expedition.

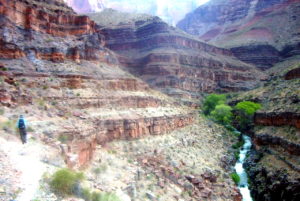

The first couple of days we drifted along, taking in the view

nd sleeping on sandbars, which have become geological features now that floods don’t rearrange them every winter.

Perennials, which never used to have a chance, have taken root

creating homes for highly-endangered willow flycatchers which, in the past, refused to come anywhere near the Canyon. (There may be an intermediate step here involving willow flies, but I’m no entomologist.)

Most of the hikes are on the north side of the river because the North Rim is 600 feet higher than the South Rim and, ecologically speaking, entirely different. To the south, desert and scrub vegetation extend all the way to Mexico City. North are mountains and forests and, at least in April,

snow-fed creeks that plunge right into the canyon,

We’d head downriver a few miles, stop, and hike. The hikes were two, or three, or four hours long. Sometimes a couple or three a day. Often up side canyons. Sometimes along broad creek beds

or beneath overhangs

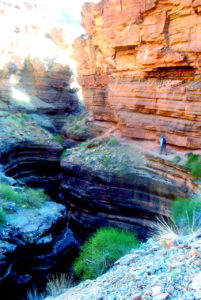

cut through sheer-sided red cliffs

that look like miniatures of the Canyon itself.

Sometimes creeks slice through polished rock

in cuts so narrow hikers have to clamber up the sides in order to turn and squeeze through.

At Carbonate Creek the trail follows a deep, echoing canyon

until it’s blocked by a dry waterfall hikers have to scale.

Even in April there are lots of dry waterfalls to get past.

We swam, some. People who hike in the Canyon in July and August probably swim a lot. But not us. Not in April. The river was too damn cold, which was not a problem Powell encountered. The water coming out of the bottom of the Glen Canyon Dam is forty-six degrees.

It’s also a beautiful, glacier-lake green instead of the mud color Spaniards named the river for. Which means the native chub, razorback suckers, and Colorado squawfish have been replaced by trout. And bald eagles are wintering over to and eat the trout.

At Travertine Canyon, crossing another dry waterfall

leads to a dimly lit cavern with a pretty stream tumbling down the back.

Getting up the Havasu River

involves working your way along the canyon wall,

which I don’t recall seeming nearly as dicey as it looks in the picture.

Although the Grand Canyon is a mere seventeen-million years old, the rock it’s made of goes way back. And a lot isn’t there at all. There’s a place you can touch 575 million-year-old Tapeats sandstone lying directly on top of 1.6 billion-year-old Vishnu Basement rock. The span of a billion years beneath the palm of your hand.

When the boat arrived at Tapeats Creek all of us except Wilma, a tough, middle-aged lady from deepest Arkansas who’d been on this trip before and knew knew what to expect, got off and began working our way along a rocky bench.

Then up an endless series of switchbacks until we reached the source at Thunder Springs: a fire hose of water

shooting out of the canyon wall. I’d never seen anything like it.

Thunder Springs would have been a very good place to call it a hike and turn around and head back to the boat. But the boat, and Wilma, had gone ahead to meet us on the far side of a broad bend in the river.

The switchbacks continued their weary way up, and up, and up until, at about 1700 feet above the Colorado we came to the top. And hours of hiking across full-on Arizona desert.

Much, much later . . . weeks later, it seemed. Months, maybe . . . we were descending the far side of a ridge when

way off in the distance Peggy spotted a shaggy figure working its way up the trail toward us. A very scruffy, scraggly-bearded, shaggy street-person sort of figure in shoulder-high brush.

Peggy raced ahead and, while I watched from hundreds of yards back, gave the figure a hug. A lone derelict wandering the desert, and there was Peggy chatting with him and leaving me wondering, How come I don’t get to do that, run up and hug strange women? But it turned out he wasn’t strange, at least if you didn’t care about appearances. He was a doctor she worked with. A very shaggy doctor off on a photo safari.

Afterwards, we were descending Deer Creek, a beautiful stream dashing along a deep chasm

and, to my mind the loveliest place in the entire Grand Canyon. But that might have something to do with how glad I was to see it. We followed it down to the river, our boat, and Wilma.

Of all the unexpected things we encountered in the Grand Canyon, the most unexpected were the traces of the people who preceded us. Not sun-addled hermits hiding from society. Not even detritus from the generations of rafters who’d preceded us. The fact is, rafters don’t leave anything at all, the Park Service is very specific about that. The Grand Canyon may be the only place on Earth where people pay money to drift down a river in the company of a large vat of their own waste. The traces we saw were from ancient peoples, from societies who’d lived in the Canyon hundreds, maybe thousands of years before.

There were petroglyphs

and granaries built into the canyon wall.

And there were potsherds . . . many, many potsherds . . . strewn among ancient household implements

still there after untold thousands of outsiders had passed through. The Park Service doesn’t let you don’t take anything out, either.

There’s no phone coverage in the Grand Canyon. Or internet. Or television. And no news from the outside. The world could end you wouldn’t hear about it until you came out.

It never occurred to Peg and me that things might work the other way, as well. But when we were disembarking at Lake Mead, and while Wilma was flipping me off for stepping on her hand, a guy who hadn’t said much during the trip mentioned to Peggy that he was nervous about what he might not have heard. It turned out he was the CFO of Bethlehem Steel, had taken the company through bankruptcy to avoid honoring its pension plans and, steelworkers being who they are, decided it was a good idea to disappear down a hole.

No Comments