10 Sep Pelelieu — Locked out in Palau

If Ireland is 40 shades of green, Palau is a hundred.

Besides the four main islands, there are something like 800 Rock Islands

scattered across the Philippine Sea a few degrees north of New Guinea. The Rock

Islands consist of sheer, limestone cliffs

undercut by ocean and topped with jungle. Nobody knows how many there are because

the number keeps changing. Sometimes, an entire island sheers apart,

.

creating two islands. Other times so much island sheers off that the place ceases to be an island at all.

In places, the sea erodes caves into the limestone, or an entire island into an arch.

In some caves you can glimpse detritus left behind by the Japanese army. A cache of 55-gallon fuel drum

or a collapsed coastal-defense gun.

Near the Rock Islands, and around them, are some of the world’s great SCUBA-diving sites . . . Blue Corner. German Channel. A saltwater lake filled with stingless jellyfish. Or so we were told. Peg and I can’t attest to it, having been barred from entering the water.

The paramount chief dropped dead while we were on the way from Guam. Which caused those in charge to decree one-hundred days of enforced mourning. No dancing. No loud music. No whatever-else-anybody-might-enjoy. To make sure nobody was diving, they dispatched boats to pull divers off the reefs. For one-hundred says the Corner was to remain Blue, the Channel exclusively German, and the jellyfish to their own devices.

Lucky for us, the dead chief hadn’t been chief of the whole shebang, just most of the shebang, which left some not-so-renowned dive spots at the far end of the archipelago for Peg and me. Getting there is why we spent so much time motoring there and back through the Rock Islands.

One of the places we were allowed to dive was Orange Beach on Pelelieu.

Whatever Orange Beach was called before the 5th Marines came ashore in September of ‘44 for one of the bloodiest, most squalid, battles of the second World War, it’s Orange Beach, now. And will stay Orange Beach as long as there are United States Marines. And Americans to remember what our Marines did there. How strange it must have seemed, fighting such a battle in such a beautiful part of the world.

Seventy-eight years later, remnants of that fight are still scattered beneath the ocean. Toppled over deck guns.

.

Coral encrusted tracked vehicles.

Steel cages that I took to be the wheelhouses of landing craft; mortar tubes; unexploded, coral-encrusted artillery shells.

Before the war, Pelelieu supported four villages. The Japanese evacuated the residents, saying it was to protect them from Americans. What the residents say is that the Japanese didn’t want anybody around to spill the beans about the fortifications. After the war, America returned the islanders to the single village they live in now. That wasn’t bureaucratic laziness, it was because the rest of Pelelieu had become uninhabitable.

Three days of naval artillery did almost nothing to soften Japanese resistance. They waited out the bombardment in tunnels carved into the limestone. Then, when the marines were ashore, came out at night to fight on terrain they knew intimately. Daytime temperatures reached 115. At night they fell to 102. The marines, carrying a pair of half-gallon canteens, were out of water by noon the first day and dropped from heat exhaustion more frequently than from Japanese bullets, mortars and artillery, although there were more than enough of those, too.

The tunnels were fitted with concealed entrances

protected by steel doors that opened to allow 200 mm guns to roll out on tracks, fire a single round, then roll back as the doors closed.

The only road in from the beach ran alongside a cliff studded with loopholes for the defenders to shoot out of

or toss grenades from.

And the Japanese did something else, something a democracy would have trouble explaining to its people. They sent their men to Pelelieu to die. They sent entire regiments . . . regiments that had earned glory in every modern war Japan fought . . . the Invasion of Taiwan, the Battle of Ganghwa, the Southwestern War, the First Sino-Japanese War, the Second Invasion of Taiwan, the Boxer Rebellion, the Russo-Japanese War, the Battle of Namdaemun and on and on through World War I right up to the Pacific War against the Americans . . . to to die on Pelelieu because their government had more important things to do than bring them home.

It’s hard for an American of my generation to work up much sympathy for Japanese soldiers, but after a few hours on the island you begin to feel something. The tunnels are low and dark and dirty,

and life inside must have been pretty unpleasant waiting there to die. Sometimes, you come across empty sake bottles

and it crosses your mind that real people lived here, scared and lonely and, probably, in need of a drink. Or, more likely, that sake was part of some perverted ceremony glorifying the martial qualities of the Japanese military.

The level of care that same military reserved for its own soldiers can be estimated by the filthy niche, no bigger than a walk-in closet, that once held a surgical table. Which, given the unevenness of the floor, must have been leveled by shoving rocks under the legs. Or, maybe not. Maybe leaving it tilted allowed bodily fluids to drain into the groove in the floor and be channeled a few feet to a hole. Where they collected.

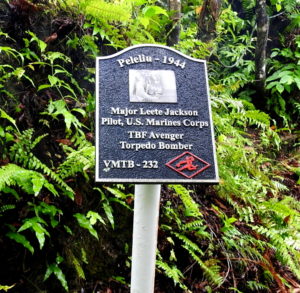

A marker, placed years later by Japanese, describes what happened when the Americans arrived:

The tunnels were bombproof and had to be taken room by room. Fighting here was vicious, using explosives, flamethrowers, burning liquid fuel and napalm. Many tunnels were sealed with machinery and explosives, entombing their combatants alive . . . The Japanese garrison numbered just over 11,000 men, of whom 19 survived.

The last defenders didn’t surrender until 1947, and only then when one of their Admirals managed to convince them the war was over.

Bloody Nose Ridge is still there, and a lot easier for an American to climb than it was in the fall of ‘44. An overgrown dirt track leads partway up, then a flight of wooden steps to a monument to the 332d Infantry.

All over the Pacific you find well-tended gardens, memorials to our soldiers,

sometimes to a single individual.

Not so much for the Japanese. And not just because they lost. Where we have been scouring Vietnam for fifty years reclaiming the remains of our fallen, you can dive Truk Lagoon and still see the bones of Japanese sailors littering the sand, or inside sunken ships.

On Pelelieu there’s a single, well-kept Japanese memorial,

the one with the plaque. But there are others, smaller shrines placed in the jungle by family members, I supposed. We passed one, long-forgotten with a tumbled-over votive dish that even I felt the need to set right, and place a flower in.

One of the striking things about Pelelieu is how thoroughly the jungle has come back. The bitterest battle on the island took place at the airstrip and the nearby Air Defense Headquarters, a concrete, almost invulnerable building. A fuzzy old photo shows how it looked in 1945.

Now, with a banyan tree twisting down from the second floor,

it looks like nothing so much as one of those jungle-reclaimed temples in Cambodia.

That all that growth and replenishment would have taken place during the lifetime of some of the people who were there makes me think . . . well, I don’t know what, exactly, it makes me think. But it does make me feel good

The airstrip itself has never gone out of use, first by the Army Air Corps and, later, as a way for important people to visit Pelelieu without troubling themselves to boat through the Rock Islands, as the Emperor of Japan recently did when he flew in for a ceremony, then back out without visiting the sites where so many of his countrymen died in the name of an earlier emperor. The word now is that the landing strip is being expanded to handle military cargo jets. Something to do with China, we were told.

No Comments