09 Jul Pamplona — Nobody Runs with the Bulls

For centuries, nobody was supposed to run with the bulls at Pamplona. Not that lots of people didn’t do it anyway.

And they’ve been doing it for a long time. The tradition kicked off in the Thirteen-Hundreds as a way of honoring St Fermin, a local boy who, nine-hundred years earlier, had emigrated to Amiens to convert the Gauls. Somehow, his festival got mixed up with the cattle market, bull fights became involved and, bulls living outside of town, had to run through the streets if they wanted to participate in the festivities.

There’s nothing like a herd of Spanish fighting bulls charging past to set young men’s hearts a-pumping and they’d run along, too. Which stimulated the city fathers to pass ordinances attempting to reign in the animal spirits of their younger, more male, citizens. Generations later, in a fit of civic common sense, the city realized there was more profit in going with the flow than trying to stem it, and turned the event into a tourist attraction . . . with the occasional tossed young man serving to increase the commercial potential.

The whole running-of-the bulls thing isn’t necessary, anymore . . . not to get into town, anyway . . . because the bulls are already there, having unloaded from a truck into a pen.

When the gate opens a rocket goes off, the bulls charge out and uphill, and the whole spectacular is broadcast to a breathless world by mobile cameras racing along overhead cables.

The entire process, from the time the bulls leave the pen until the last couple of rockets go off welcoming them into the bullring, scarcely lasts three or four minutes each morning.

With nothing much for people to do the rest of the time, the remainder of the festival turns into the kind of week-long frat party that draws unwelcome attention from the dean. Old people, young people, kids, everybody, dresses for the occasion in their finest bull-running whites, set off with the red scarves beloved by San Fermin.

Even those who can’t make it into the plaza because civic patriotism demands they serve drinks to the revelers

dress in the spirit of the occasion.

Hemingway spent a lot of time in Pamplona, and you can see pictures of him

gracing shop windows, but he didn’t even pretend to run with the bulls. The fact is, nobody runs with the bulls because nobody can. Bulls are way too fast. Saying you ran with the bulls at Pamplona is like saying you ran with the semis on the Interstate.

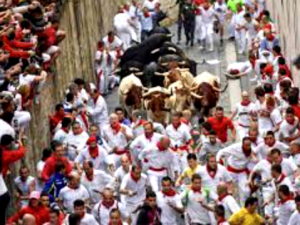

What people actually do is, hours ahead of time, slide through the wooden barriers that separate the narrow alleyways the bulls run along,

from the rest of the city, go into series of stretches and squats like Olympic athletes warming up for the triathlon; mug for cameras; shout to their buddies; squirt long streams of cheap wine into their mouths; crane their necks down the street in case a bull may have gotten loose ahead of the rocket and, when the bulls really do get out, cower back against the wall.

Even when it’s just steers running by. Then, when the coast is clear, traipse along behind to the bullring.

There’s a stretch where the passage widens and so many revelers congregate

that there isn’t enough wall for everybody to flatten against, and some of the rowdier participants attempt to count coup

by drunkenly slapping at bulls as they run by.

Sometimes, tramplings happen, but rarely gorings because the lead animals aren’t hair-tempered Spanish Fighting Bulls. They’re mild-mannered steers not interested in poking holes in partygoers. Although gorings are the major spectator draw, the year we were there only one person managed to pull it off, which he accomplished by walking up to a bull already in the ring, turning his back, and taking a selfie.

I can cower against a wall as well as the next guy, I thought. I’d packed a pair of khaki pants, an old, white shirt and an out-of-date red tie in the bottom of my carry-on where Peggy wouldn’t notice. Running with the bulls at Pamplona is something wives tend to frown on, and I didn’t want any arguments.

I would have, too, if it hadn’t been for about a pound of improperly smoked salmon I’d downed in the Madrid airport while watching the Women’s World Cup finals between the US and Spain. Which turned my strongest memories of Pamplona intowhat I could see from the hotel window between trips to the bathroom. Looking back, maybe getting salmon-poisoned wasn’t as haphazard as it seemed. After all, I was rooting against Spain . . . and in favor of women the French newspapers had dubbed Les Ogres.

Every night

the sky was a dazzle of fireworks

while, during the day,

the plaza thronged with the sort of carouser who made cowering against a wall with bulls running by entertaining for the rest of us.

For something so seemingly chaotic, the festival is all very carefully choreographed. Fireworks launched at the same time every evening. Religious processions

proceeded at the same time every day.

Mock bullfights

for kids took place in the streets below our window at the same time and, judging by the noise, the same bands playing the same tunes marched by every night, all night, at the same times . . . so that visitors who could only spend a day or two in town could return home with the whole Pamplona experience.

No Comments