27 May Paris — Improving the Empire of the Dead

A long time ago my mother died in Paris, and I thought she might have wound up in the Catacombs, because people still do. So when Peggy and I were in the area, we descended into the Catacombs to check out how things were down there.

Nowadays, Parisians are laid to rest in small churchyards around the city, but nobody owns a burial plot. They rent them for what, before euros, was five francs every twenty years. Pretty much everybody has that kind of money, so you’d think the cemeteries would fill up. But families move. Or die out. Or just kind of lose track, like we did. Rents fall into arrears, tenants get relocated, and space opens up. Where the deceased get relocated to is a series of mine shafts left over from quarrying limestone for the city walls.

Before Paris became Paris, it was Lutetia, and the Lutetians didn’t have a cemetery problem. Being Romans, and, therefore, practical, they buried their dead outside the walls where the graves could expand as far as needed into the Gaulish countryside. But the Roman Empire fell, Lutetia became Paris, and the Franks located their cemeteries in the middle of town.

The city kept growing, people kept dying and, by 1780, the graveyard at St Innocents . . . which was right next to the central market . . . was oozing bodies. Ground level had risen two meters above the adjoining streets, the district reeked of rotting flesh, and a wall gave way . . . flooding a neighboring basement with half-rotted cadavers. Even Louis XVI could see that something had to be done.

What was done was a hole punched through to the mine shafts. Then, starting at sunset and running all night for eighteen months, wagons draped with black cloth and accompanied by torch bearers and priests chanting the Requiem, carried two million bodies from St Innocents to the hole. And dropped them down. The wagons must been groaning because, during the year and a half it took to empty St Innocents, they moved close to 3700 bodies a night. Followed by another four million from the other cemeteries. The gravestones, carved scenes of the Gates of Heaven, and other monumental what-nots wound up in a museum.

With the cemetery situation sorted out, the City of Lights turned its attention to the living, the Revolution arrived, and matters above ground became as confused as the heap of bones in the mine shaft.

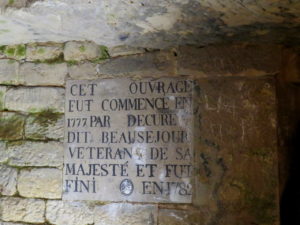

Things rocked along until 1810 when the Director of the Paris Mine Inspection Service decided to turn the place into a presentable mausoleum, and ordered the bones and skulls organized into the walls

and fanciful arrangements

they’re still in . . . all labeled with the names of the churchyards they came from,

or the conflict they died in,

chiseled in limestone. Even with all that, it was hard for Peggy and me to recognize who any particular set of bones once belonged to.

As visual adornments,

the Director installed the cemetery decorations

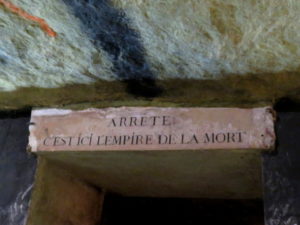

that managed to survive the Revolution, along with signs warning

“Stop! This is the empire of Death.” The message made all the more chilling under the flickering candlelight of the time.

So that visitors could wander the Catacombs as easily as strolling the boulevards above, the Director posted more signs, naming whatever feature of Paris happened to be overhead.

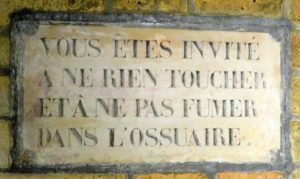

In more modern times, signs cautioning visitors against smoking,

have been carefully carved out of limestone to give, one imagines, the impression that not-smoking dates back to Napoleon.

Recently, cheap, metal signs in the lingua franca of modern hieroglyphs

have been added for the convenience of people who don’t speak French and who, otherwise,

wouldn’t understand what the signs were telling them not to do.

And, so the Catacombs remain to this day.

Sort of.

Because it turns out that the Paris Mine Inspection Service wasn’t the only outfit determined to add a bit of life to the Empire of Death. A secret society calling itself les UX, for “Urban Experiment,” took a shot at it, too. But being French, and knowing French bureaucrats to be French bureaucrats, didn’t mention it to the authorities.

A lot of people seemed to have been in the loop, though, because the movie theater the police discovered in 2004 gave every impression of having been used for a long time. Along with reels of Films noir and modern-day thrillers, the theater sported projection equipment, a giant screen, seats for the audience, a restaurant with tables and chairs, and a fully stocked bar. Mother always liked movies. I think she would enjoy having a little Parisian dîner-théâtre in the neighborhood.

No Comments