27 Feb Botswana — Pirated Movies From The Pakistani

One of the many nice things about living in Africa was the movies. In South Africa, or Morocco, or pretty much anywhere else, you could pick up the newest Tom Cruise blockbuster, or any other first run movie, weeks before it hit the theaters in America. And for a lot less money. Ten pula, in Botswana: a buck and a quarter for a DVD, which was way less than the folks in the States were going to pay when the movie finally lagged its way into the multiplexes.

I bought mine at a women’s clothing store run by a Pakistani in an obscure mall I only visited one other time, and that was to meet the Chinese ambassador at an equally obscure restaurant for dinner. I learned about the Pakistani from folks at the embassy who were a lot more sophisticated in the ways of pirated movies than I was.

He kept the DVD’s stashed in shoe boxes behind a counter next to racks of plastic purses and glittery pretend jewelry. The first time I visited I spent hours thumbing through those boxes while trying to stay out of the way of ladies shopping for clothing. I bought so many DVD’s I got a volume discount.

They were a sweet deal and fun to watch. Sometimes, a little banner would scroll across the top of the screen:

. . . FOR REVIEW PURPOSES ONLY, NOT TO BE SOLD . . . THIS DISK IS FOR REVIEW PURPOSES . . .

followed by scary-looking warnings about the FBI, which didn’t sound all that scary with the FBI eight-thousand miles away.

Movies that had already appeared in theaters specialized in the total cinematic experience. Disks often contained 18 full-length films (a bargain at just over six cents a movie) where you could see people sitting in front of you. Every now and then, one would stand up and make his way to the aisle. Only to return a few minutes later with popcorn and a soft drink.

Once, a theater got raided and everybody jumped up and ran around screaming, the video gave a little jerk and the movie picked back up in a different theater. You could tell it was a different theater because the exit signs weren’t in the same places, but no matter. The pirate wasn’t about to sell half a movie. He had his good name to protect.

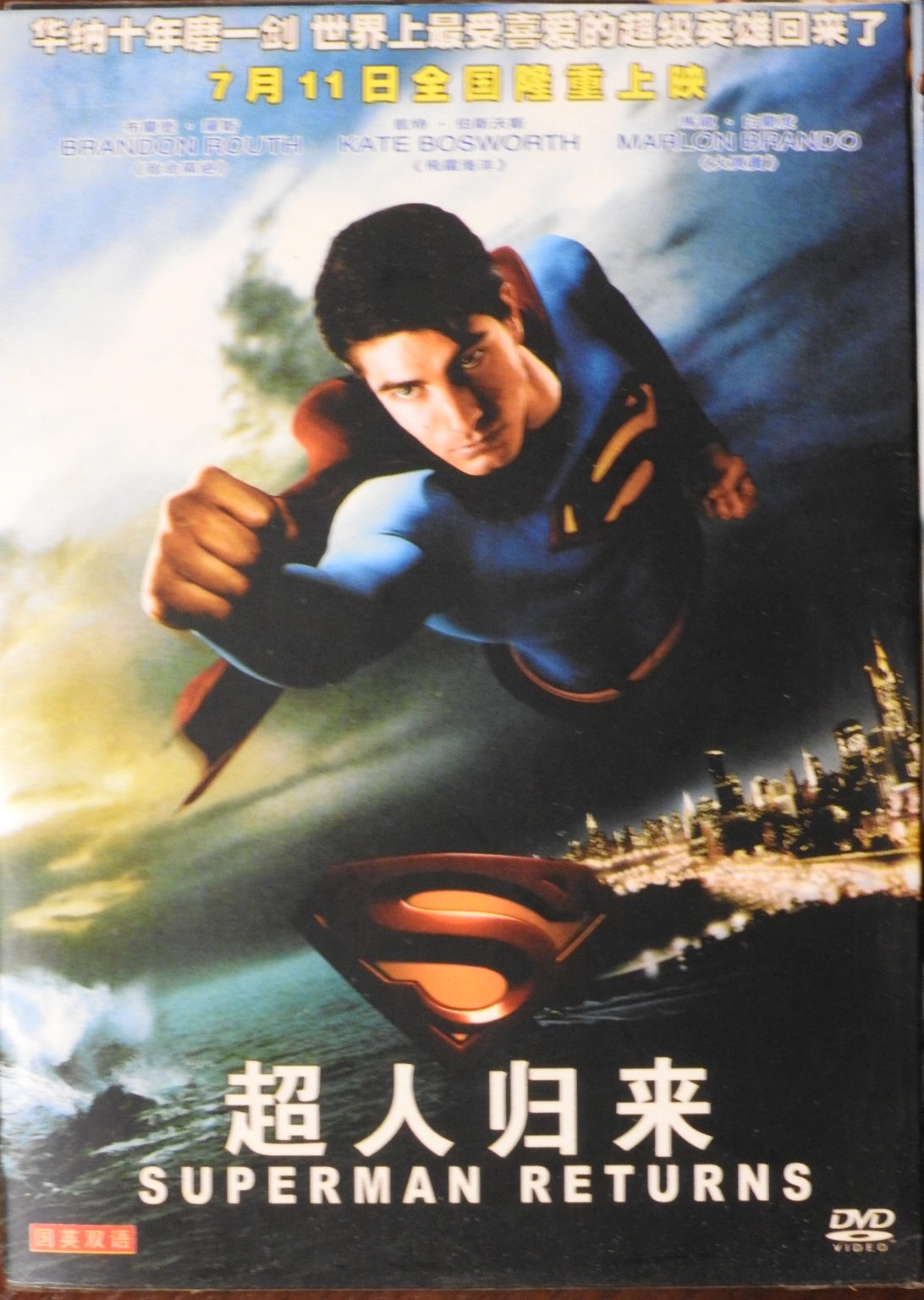

Pirates build loyal followings by branding their disks with riffs on labels from better-known products. Sutra Collections, for instance, issues its thirty-movie disks (3 cents a movie) beneath the red, white and blue NBA logo,

only with the basketball replaced by a tiny DVD.

The Sexy Goddess SUFEIMASUO FILM SET, showcasing such erotic classics as Anna Karenina, comes emblazoned with the word “Ma” superimposed over an apple. In a bit of design prestidigitation that surely would have appealed to Steve Jobs, the bite out of the apple forms the “C” in MaC.”

All of which would be persuasive if it weren’t for the Chinese characters also on the package.

One day when I went down to the Pakistani’s to check out the movies that hadn’t been released in theaters yet, he motioned me to hide behind a rack of blouses while a couple of ladies finished shopping. They were pink blouses tastefully festooned with sequins.

When the ladies had left, he had me squat out of sight behind the counter while I thumbed through the shoeboxes. For ten years Botswana had been a member of the International Copyright Convention, but hadn’t made a big deal about it. Now it was turning up the heat, and the Pakistani was not happy.

“I paid good money for a license to sell these movies,” he thumped a piece of paper taped beside the register.

The government had been quite straightforward about it:

PERMIT TO TRAFFIC IN PIRATED MOVIES

the license said. Or something along those lines.

“I sell a lot of these,” the Pakistani said.”

“You’re famous for it.”

“And now I’m not supposed to?”

“The police must know what you do,” I said, thinking of all the people at the embassy who knew what he did.

“They raid me sometimes.”

I was beginning to think I’d better stock up. There was no telling how much longer those shoeboxes were going to be there, and laid a handful of DVD’s next to the register.

The Pakistani rang them up with a mournful look, as if the country he loved was changing in ways he didn’t understand. “I don’t know why they keep pestering me,” he said. “They never find anything. I go to the same mosque as the Minister of Justice and he lets me know when a raid’s scheduled.”

Understandable as his grievance was, it was hard to be bullish about long-term viability for the pirated DVD business, what with the rising popularity of streaming services. Then, on the third and fourth days of this month, the prospects turned much worse. The Chinese government busted fourteen people in Shanghai for copyright infringement.

Copyright infringement?

In China?

In a country that’s labored for decades to brand itself as the premier nation in the world for stealing intellectual property?

The thing is, it wasn’t the integrity of the commercial system the Chinese government was worried about. It was the integrity of their crusade to isolate their people from everybody else in the world. The fourteen copyright violators were translators for a streaming service called Renren Yingshi, “Everyone’s Movies and Shows,” which had provided something like twenty-thousand Western movies and television programs to Chinese viewers.

Along with North Korea, Syria and, Russian-controlled Crimea, China is one of four places on Earth without Netflix. Which means that pirated movies and television shows aren’t just a convenience for culturally deprived expats. They are the only glimpses into Western culture for hundreds of millions of people trapped behind the Great Firewall. And subtitles are what make it all happen.

According to Yan Feng of Fudan University, subtitling pirated movies has turned into one of the great translation projects in Chinese history, right up there with the program in the nineteenth century to translate Western literature into Chinese.

The subtitles are provided by volunteers working for “Translation Groups.” The groups are very selective, volunteers are usually paid with nothing more than on-screen credits, and their subtitles are excellent . . . as opposed to those from the official censors on the very few foreign films actually allowed in the country, which are so heavy-handed that shows like “Game of Thrones” with complex plots become incomprehensible.

As the Economist (20 February) put it, Chinese viewers have been referring to the crackdown on the Translation Groups with “the poetic term, lindong jiangshi . . . ‘winter is coming.’”

No Comments