29 Aug Egypt — Curse of the Pharaoh’s Tomb

Viewed from the outside, the Great Pyramid at Giza looks like such a heap of stone it never occurred to me that it might be possible to go inside.

To the uninitiated, it’s looked that way for more than 4500 years . . . despite the fact that people began slipping inside when the Old Kingdom collapsed and the guards went home. Those robbers must have known something because their tunnel intersected the Ascending Passage that diagonals upwards through the Great Gallery to the place Pharaoh Khufu was entombed.

Given that there’s an Ascending Passage there is, naturally enough, a Descending Passage. The Descending Passage diagonals downward to a chamber carved deep into the bedrock below the pyramid. At any other pyramid this would have been the pharaoh’s final resting place but, apparently, Khufu didn’t want to spend eternity below ground. Which explains why the King’s Chamber is high up inside the pyramid. Or it doesn’t. Nobody really knows. Maybe nobody at the time knew, either. Maybe the King’s Chamber is where it is because a willful monarch changed his mind partway through construction.

There’s a third passage that branches off from the Ascending Passage. It neither ascends nor descends but heads straight across to the Queen’s Chamber. This strikes the modern observer as odd, seeing as how the queen had her own pyramid next door.

When Herodotus came by in 445 BC the Robber’s Tunnel was sealed back up and he couldn’t get inside. The tour guides had long memories, though, and told him about it.

The pyramid was reopened in the 820’s AD by order of one Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid, the Seventh Abbasid Caliph, who became curious about the wonders that lay inside. His men built fires against the pyramid, doused the hot granite with vinegar, then sledged at the cracks with iron spikes. Like the previous robbers, these guys must have known something because they, too, managed to grope their way to the Ascending Passage. Even though the King’s Chamber had long ago been cleaned out, the caliph claimed his men were the first inside.

There’s another claim about the Great Pyramid that not many people believe: In 1798 Napoleon decided to spend the night there. Lit by a sputtering candle he made his way up the Ascending Passage, through the Grand Gallery and into the King’s Chamber. The next morning he emerged white and shaken and refusing to talk about what happened. Twenty-three years later on his death bed he finally opened up, only to sink back onto his pillow. “What’s the use?” he said. “You wouldn’t believe me anyway.”

The story about Napoleon that people do believe is that he spent part of his time in Giza calculating that if he disassembled the Great Pyramid he’d have enough stone to build a twelve-foot-high wall around France. The way things worked out later, maybe he should have given that idea more thought.

One of the nice things about modern-day Egypt: for people with money, pretty much everything is for sale. If you want to follow in the footsteps of ancient priests, and tomb robbers; Arab demolition gangs; Napoleon Bonaparte and nineteenth-century British archaeologists; all you have to do is buy a ticket.

You don’t even need to use the Robbers’ Tunnel. Like all the other tourists, I walked in through the main entrance

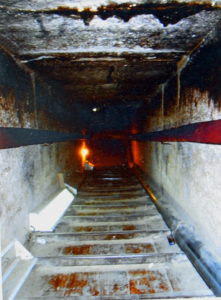

as dignified as any dead pharaoh, angled down the narrow corridor until I came to the Ascending Passage,

and ascended.

You wouldn’t think it would be possible to get turned around in a one-dimensional space but, somehow, when I reached the place where the Grand Gallery debouches into the passage to the King’s Chamber I headed back downhill into what I imagined was the very center of the pyramid. And up again toward . . . daylight.

I don’t want to sound anything less than ecumenical here, but that didn’t seem right. I knew dead pharaohs expected to ride forever across the skies with Amun-Ra, the sun god but, still, it never occurred to me that a sun god might actually have become lodged inside a pyramid. And when I poked my head out to look, I was right. There weren’t any gods out here, just the desert sun. And an Egyptian collecting tickets.

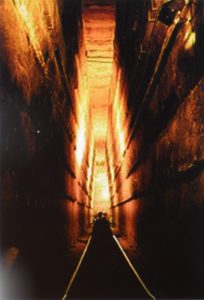

So it was back down to the Ascending Passage to try again. And up and through the Grand Gallery

and, this time, onward to the King’s Chamber.

I don’t remember what I expected to find. Plastered walls covered with paintings. Texts from the Book of the Dead. Some marks of life remaining in a room sealed off for a deceased king. What I saw, and the nineteenth-century British archaeologists who got there before me saw, and Napoleon probably saw, and Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid saw, and Herodotus would have seen if he’d been able to get inside, and the Egyptians who resealed the Robber’s Tunnel probably saw, was a battered sarcophagus chiseled out of red Granite.

The reason it’s not in the British museum is because it’s too big to descend the Ascending Passage. Which raises some questions of its own, like, “How did it get there?” The only plausible answer being that the pyramid was built around it. Which raises more questions, like, “Why?” But the real question, at least among those of us who were raised on Hollywood movies, is “Where did the mummy go?”

“And is there a curse?”

Nobody knows for sure what became of the mummy, but the curse, that’s a different story. I don’t want to sound all woo-woo and spooky here, but think about the people who ventured into the Great Pyramid over the years: The priests who laid Khufu to rest. The royal wives. The scribes and retainers. The robbers who broke in. The workmen who closed the place back up. Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid. Napoleon. All those nineteenth-century British archaeologists. They’re dead now, even Herodotus who didn’t quite make it inside, dead like every other person for the first 4400 years of the pyramid’s existence who dared enter the King’s Chamber. All dead. Every one.

No Comments